# Importing necessary libraries

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

from statsmodels.graphics.tsaplots import plot_acf, plot_pacf

from statsmodels.tsa.arima.model import ARIMA

from statsmodels.tsa.statespace.tools import diffAutocorrelation Models

IN2004B: Generation of Value with Data Analytics

Department of Industrial Engineering

Agenda

- Autocorrelation

- The ARIMA model

- The SARIMA model

Load the libraries

Before we start, let’s import the data science libraries into Python.

Here, we use specific functions from the pandas, matplotlib, seaborn, sklearn and statsmodels libraries in Python.

statsmodels library

- statsmodels is a powerful Python library for statistical modeling, data analysis, and hypothesis testing.

- It provides classes and functions for estimating statistical models.

- It is built on top of libraries such as NumPy, SciPy, and pandas

- https://www.statsmodels.org/stable/index.html

Problem with linear regression models

Linear regression models do not incorporate the dependence between consecutive values in a time series.

This is unfortunate because responses recorded over close time periods tend to be correlated. This correlation is called the autocorrelation of the time series.

Autocorrelation helps us develop a model that can make better predictions of future responses.

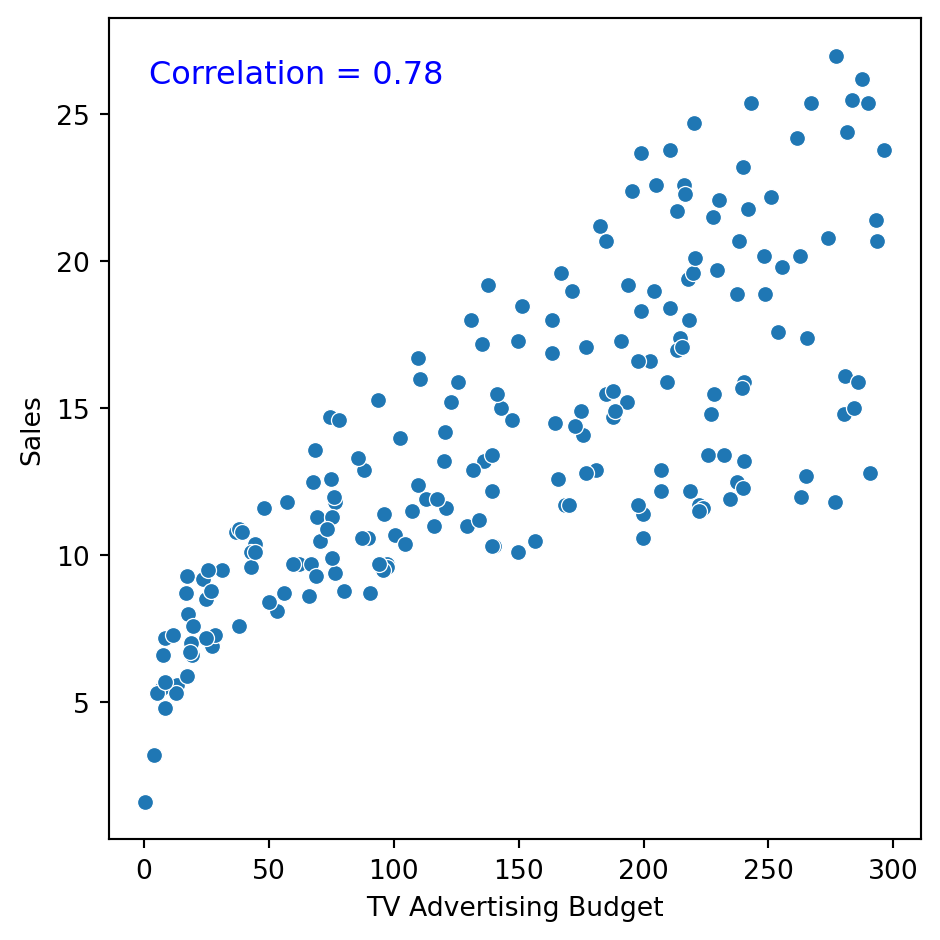

What is correlation?

It is a measure of the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two numerical variables.

Specifically, it is used to assess the relationship between two sets of observations.

Correlation is between \(-1\) and 1.

How do we measure autocorrelation?

There are two formal tools for measuring the correlation between observations in a time series:

The autocorrelation function.

The partial autocorrelation function.

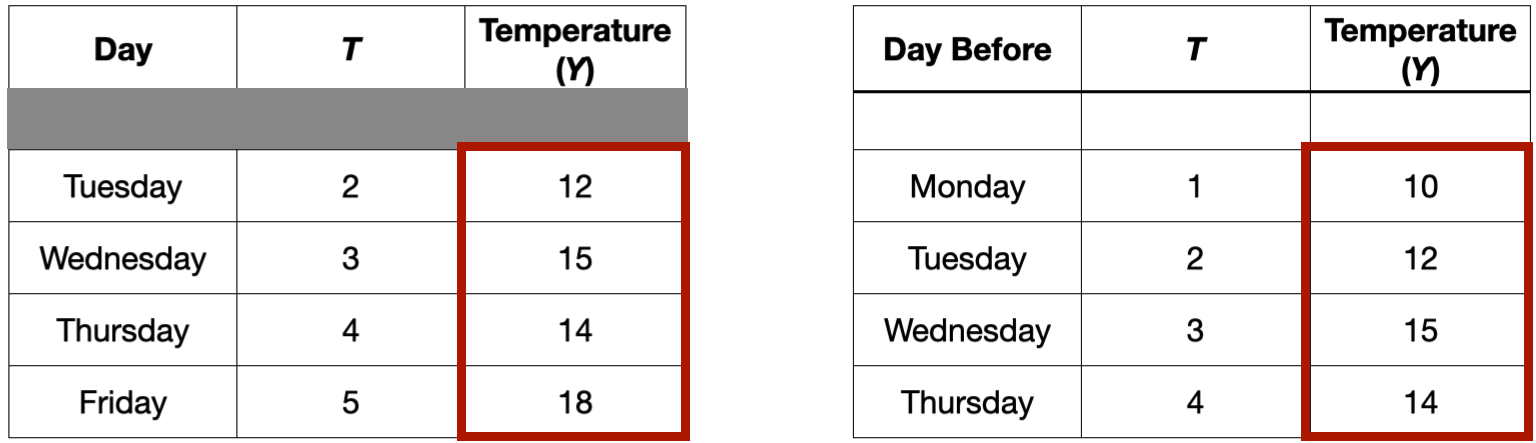

The autocorrelation function

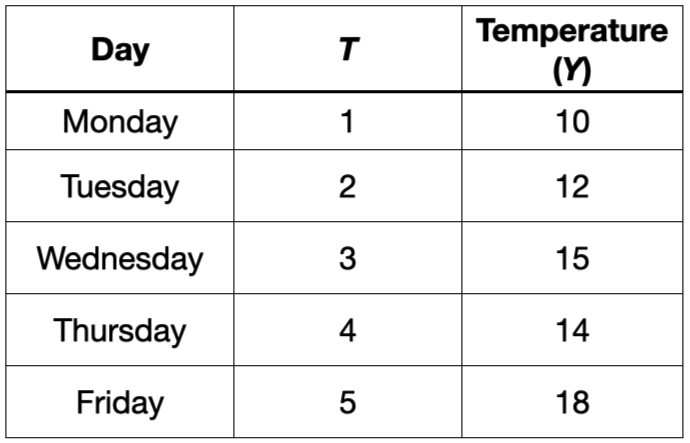

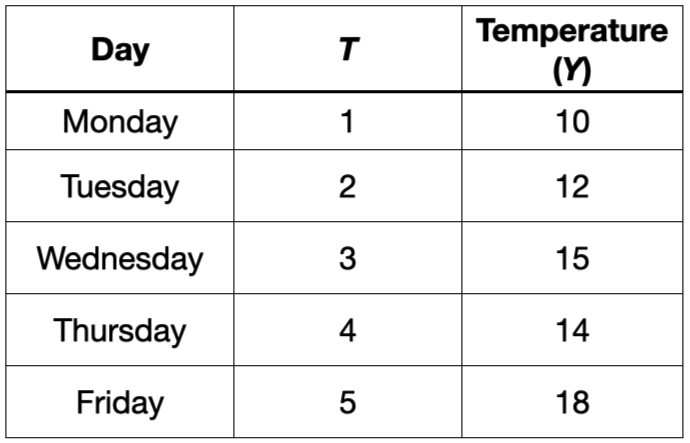

Measures the correlation between responses separated by \(j\) periods.

For example, consider the autocorrelation between the current temperature and the temperature recorded the day before.

The autocorrelation function

Measures the correlation between responses separated by \(j\) periods.

For example, consider the autocorrelation between the current temperature and the temperature recorded the day before.

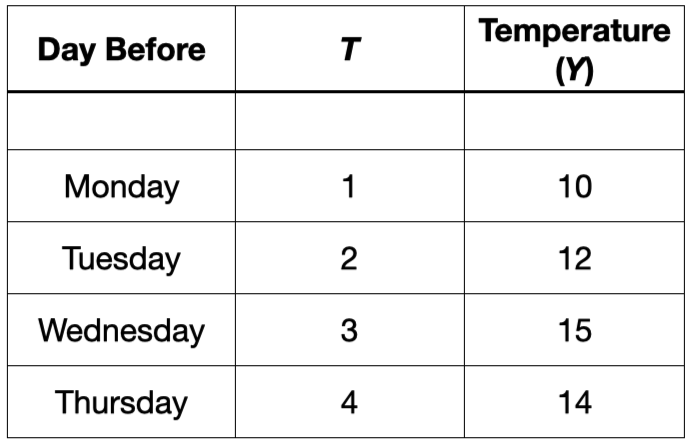

The autocorrelation function

Measures the correlation between responses separated by \(j\) periods.

For example, consider the autocorrelation between the current temperature and the temperature recorded the day before. This would be the correlation between these two columns

Example 1

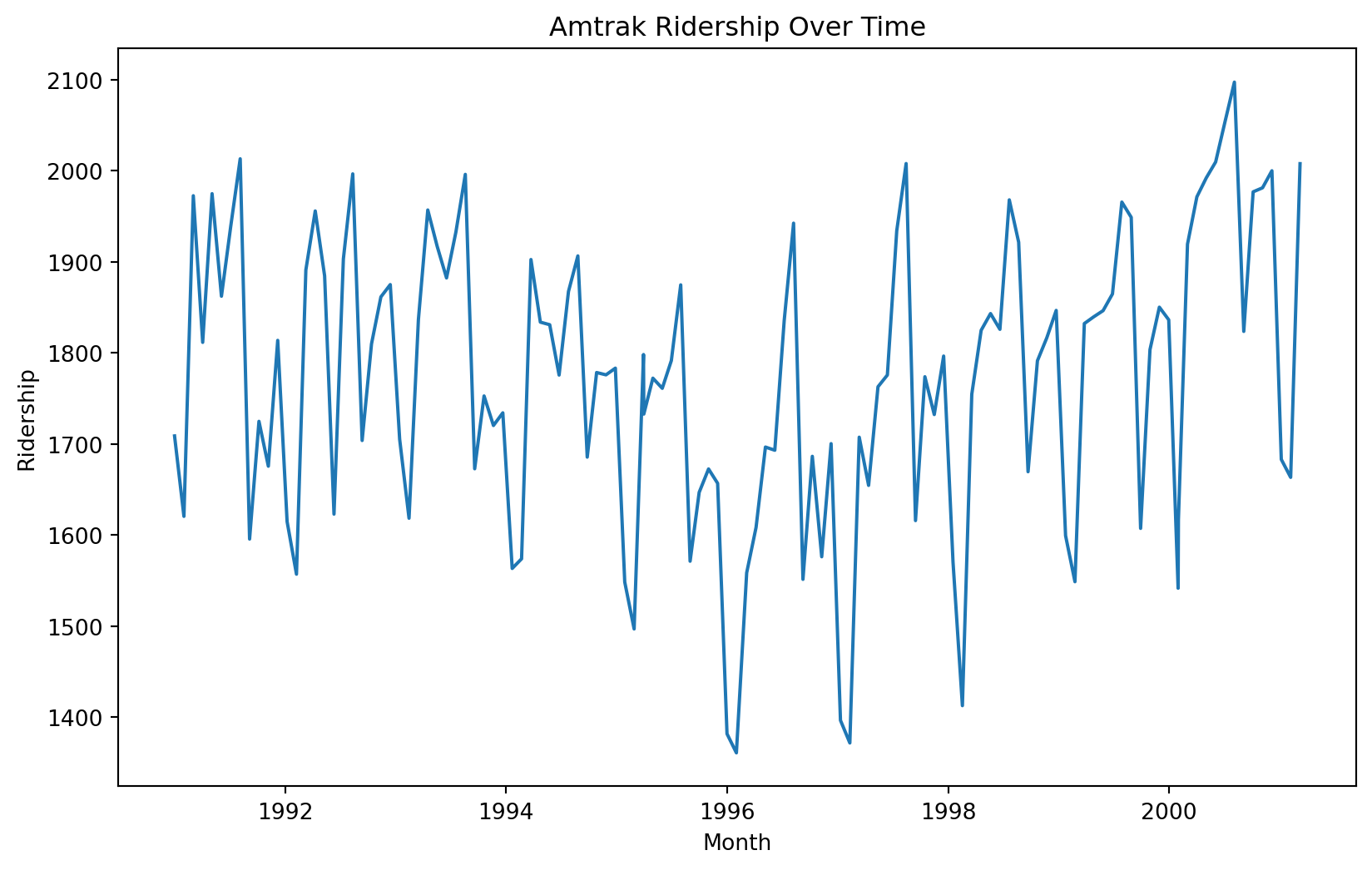

Let’s consider again the dataset in the file “Amtrak.xlsx.” The file contains records of Amtrak passenger numbers from January 1991 to March 2004.

| Month | t | Ridership (in 000s) | Season | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1991-01-01 | 1 | 1708.917 | Jan |

| 1 | 1991-02-01 | 2 | 1620.586 | Feb |

| 2 | 1991-03-04 | 3 | 1972.715 | Mar |

| 3 | 1991-04-04 | 4 | 1811.665 | Apr |

| 4 | 1991-05-05 | 5 | 1974.964 | May |

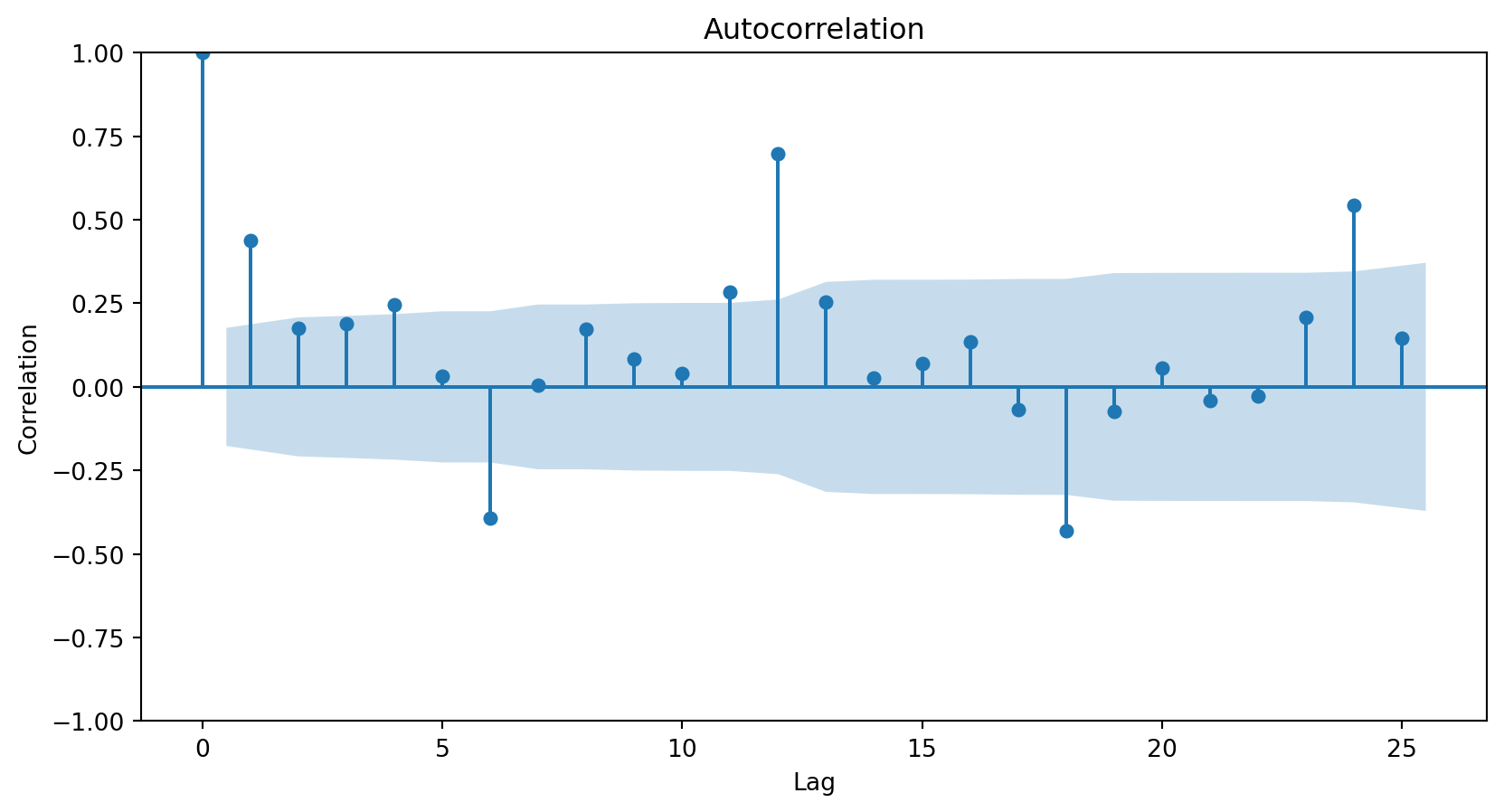

Autocorrelation function

The autocorrelation function measures the correlation between responses that are separated by a specific number of periods.

The autocorrelation function is commonly visualized using a bar chart.

The horizontal axis shows the differences (or lags) between the periods considered, and the vertical axis shows the correlations between observations at different lags.

Autocorrelation plot

In Python, we use the plot_acf function from the statsmodels library.

The lags parameter controls the number of periods for which to compute the autocorrelation function.

The resulting plot

<Figure size 960x576 with 0 Axes>

The autocorrelation plot shows that the responses and those from zero periods ago have a correlation of 1.

The autocorrelation plot shows that the responses and those from one period ago have a correlation of around 0.45.

The autocorrelation plot shows that the responses and those from 24 periods ago have a correlation of around 0.5.

<Figure size 384x384 with 0 Axes>

Autocorrelation patterns

A strong autocorrelation (positive or negative) with a lag \(j\) greater than 1 and its multiples (\(2k, 3k, \ldots\)) typically reflects a cyclical pattern or seasonality.

Positive lag-1 autocorrelation describes a series in which consecutive values generally move in the same direction.

Negative lag-1 autocorrelation reflects oscillations in the series, where high values (generally) are immediately followed by low values and vice versa.

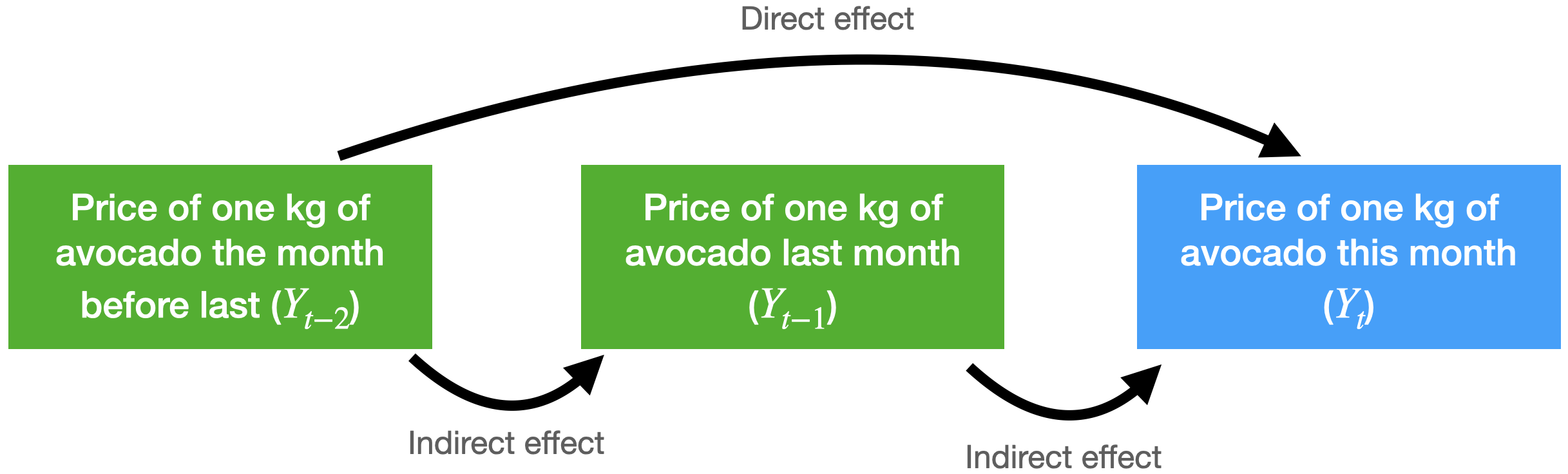

More about the autocorrelation function

Consider the problem of predicting the average price of a kilo of avocado this month.

For this, we have the average price from last month and the month before that.

The autocorrelation function for \(Y_t\) and \(Y_{t-2}\) includes the direct and indirect effect of \(Y_{t-2}\) on \(Y_t\).

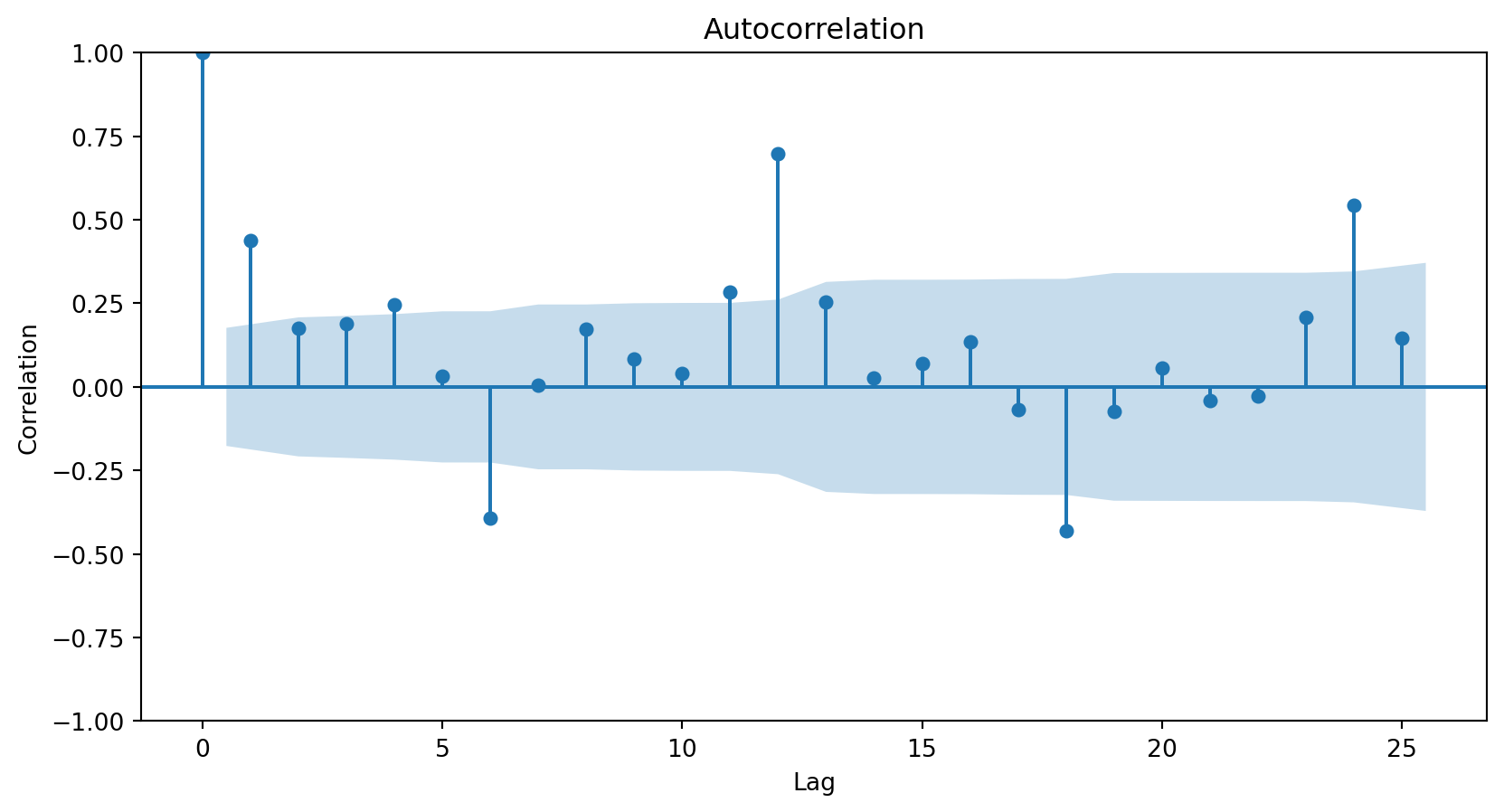

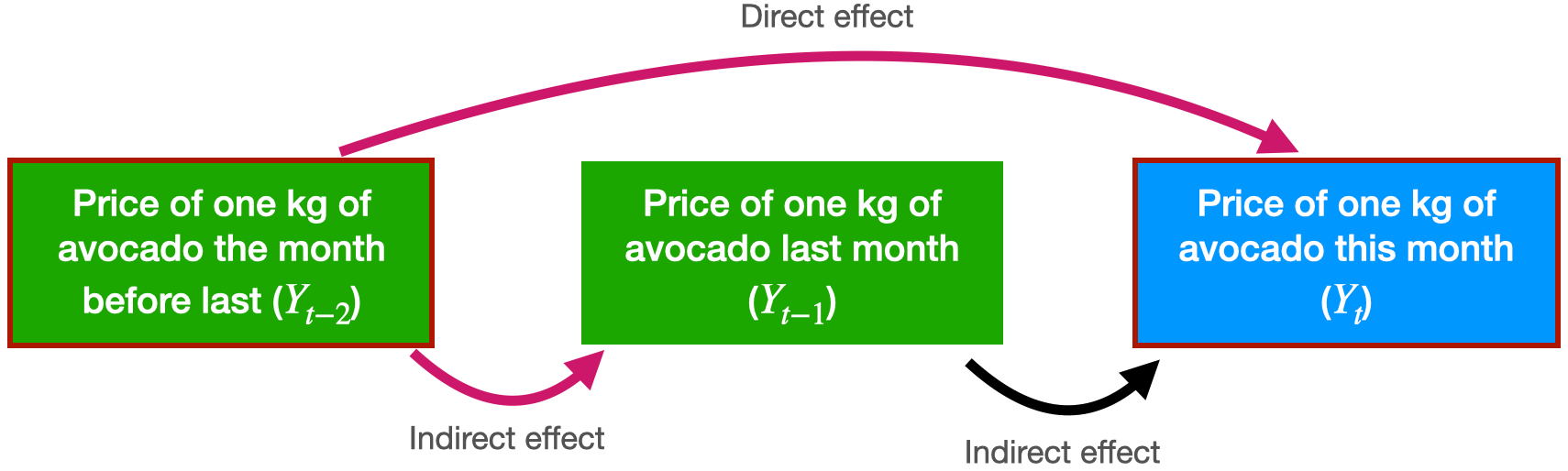

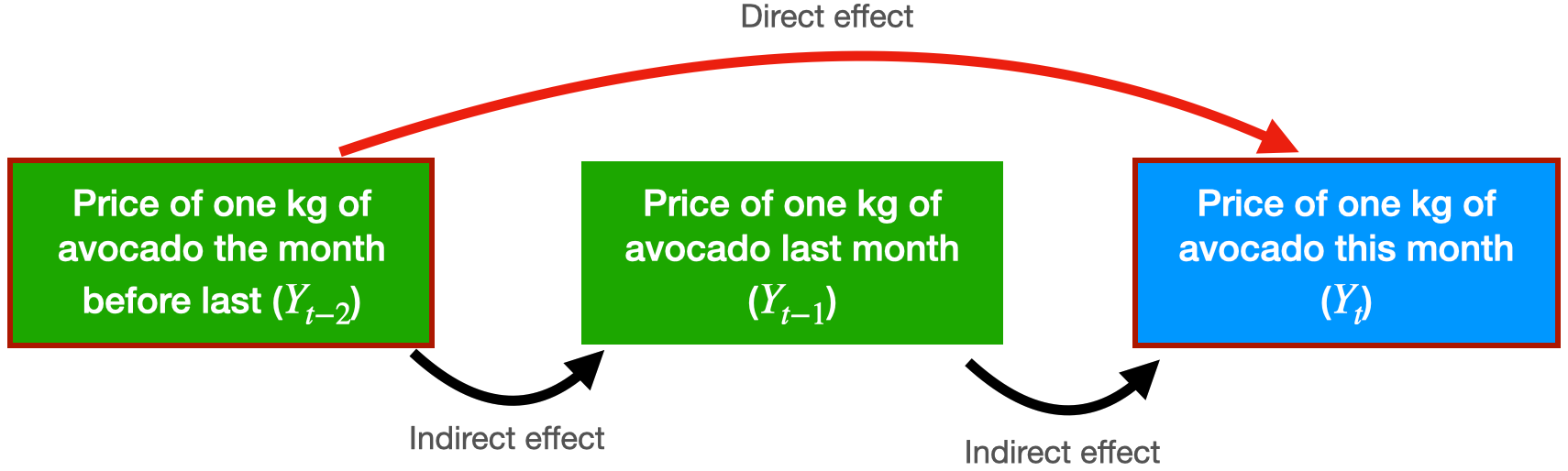

Partial autocorrelation function

Measures the correlation between responses that are separated by \(j\) periods, excluding correlation due to responses separated by intervening periods.

In technical terms, the partial autocorrelation function fits the following linear regression model

\[\hat{Y}_t = \hat{\beta}_1 Y_{t-1} + \hat{\beta}_2 Y_{t-2}\] Where:

- \(\hat{Y}_{t}\) is the predicted response at the current time (\(t\)).

- \(\hat{\beta}_1\) is the direct effect of \(Y_{t-1}\) on predicting \(Y_{t}\).

- \(\hat{\beta}_2\) is the direct effect of \(Y_{t-2}\) on predicting \(Y_{t}\).

The partial autocorrelation between \(Y_t\) and \(Y_{t-2}\) is equal to \(\hat{\beta}_2\).

The partial autocorrelation function is visualized using a graph similar to that for autocorrelation.

The vertical axis shows the differences (or lags) between the periods considered, and the horizontal axis shows the partial correlations between observations at different lags.

In Python, we use the plot_pacf function from statsmodels.

The partial autocorrelation plot shows that the responses and those from one period ago have a correlation of around 0.45. This is the same for the autocorrelation plot.

The partial autocorrelation plot shows that the responses and those from two periods ago have a correlation near 0.

<Figure size 960x576 with 0 Axes>

The ARIMA Model

Autoregressive models

Autoregressive models are a type of linear regression model that directly incorporate the autocorrelation of the time series to predict the current response.

Their main characteristic is that the predictors of the current value of the series are its past values.

An autoregressive model of order 2 has the mathematical form: \(\hat{Y}_t = \hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\beta}_1 Y_{t-1} + \hat{\beta}_2 Y_{t-2}.\)

A model of order 3 looks like this: \(\hat{Y}_t = \hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\beta}_1 Y_{t-1} + \hat{\beta}_2 Y_{t-2} + \hat{\beta}_3 Y_{t-3}.\)

ARIMA models

A special class of autoregressive models are ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average).

An ARIMA model consists of three elements:

- Integrated operators (integrated).

- Autoregressive terms (autoregressive).

- Stochastic terms (moving average).

1. Integrated or differentiated operators (I)

They create a new variable \(Z_t\), which equals the difference between the current response and the delayed response by a number of periods or lags.

There are three common levels of differentiation:

- Level 0: \(Z_t = Y_t\).

- Level 1: \(Z_t = Y_t - Y_{t-1}\).

- Level 2: \(Z_t = (Y_t - Y_{t-1}) - (Y_{t-1} - Y_{t-2})\).

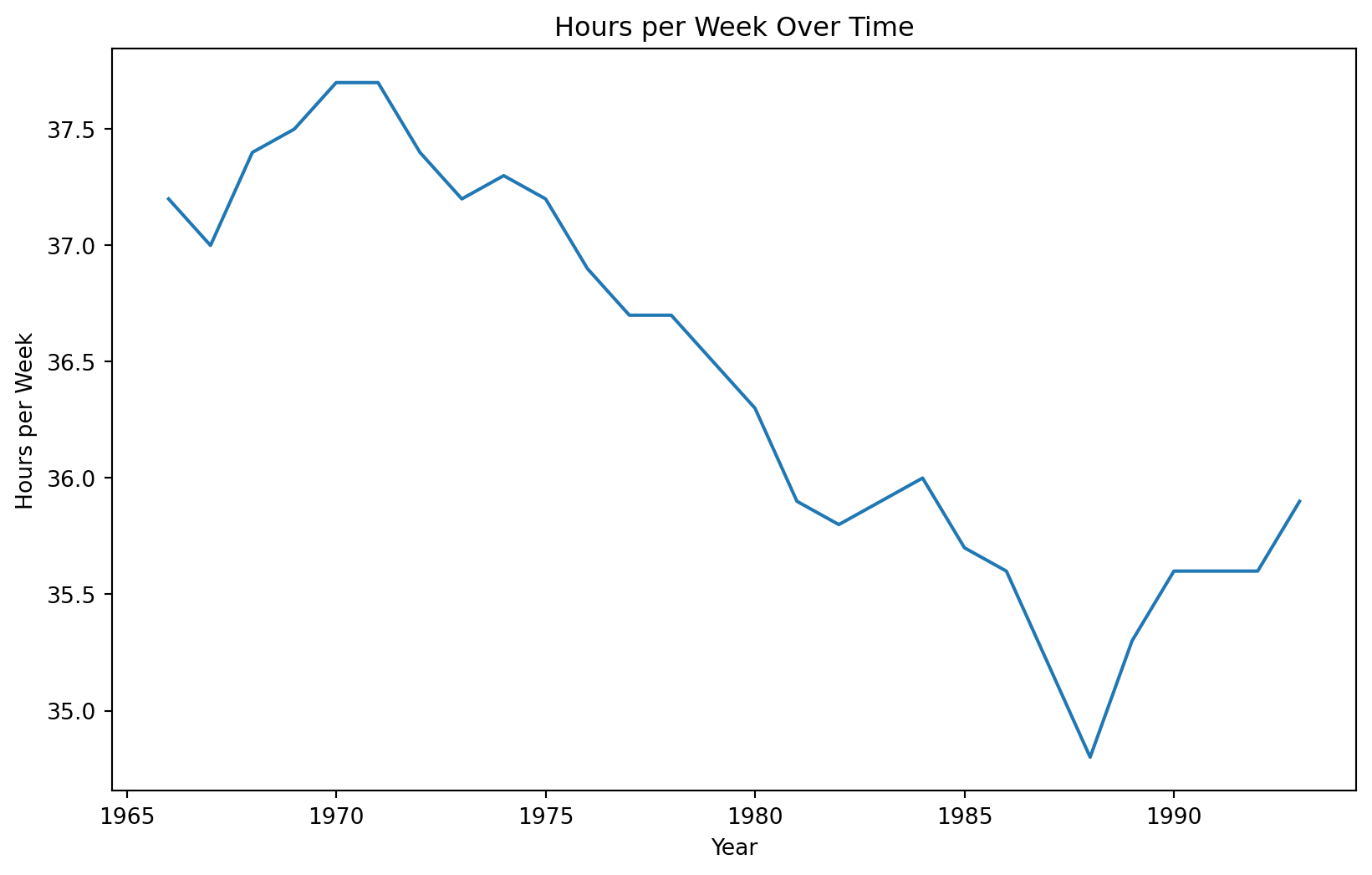

Example 2

We consider the time series “CanadianWorkHours.xlsx” that contains the average hours worked by a certain group of workers over a certain range of years.

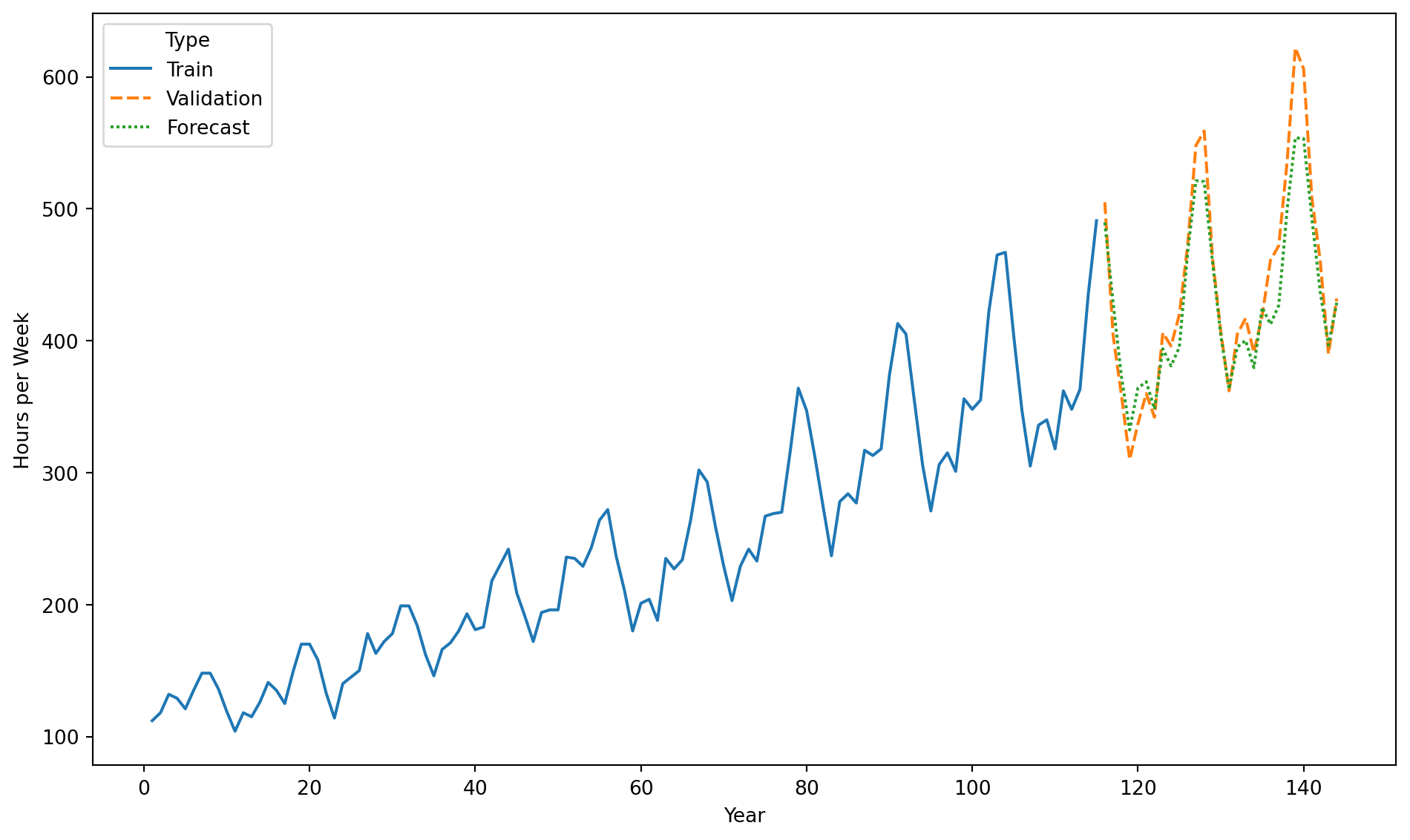

Creating a train and a validation data

Recall that we would like to train the model on earlier time periods and test it on later ones. To this end, we make the split using the code below.

We use 80% of the time series for training and the rest for validation.

Training data

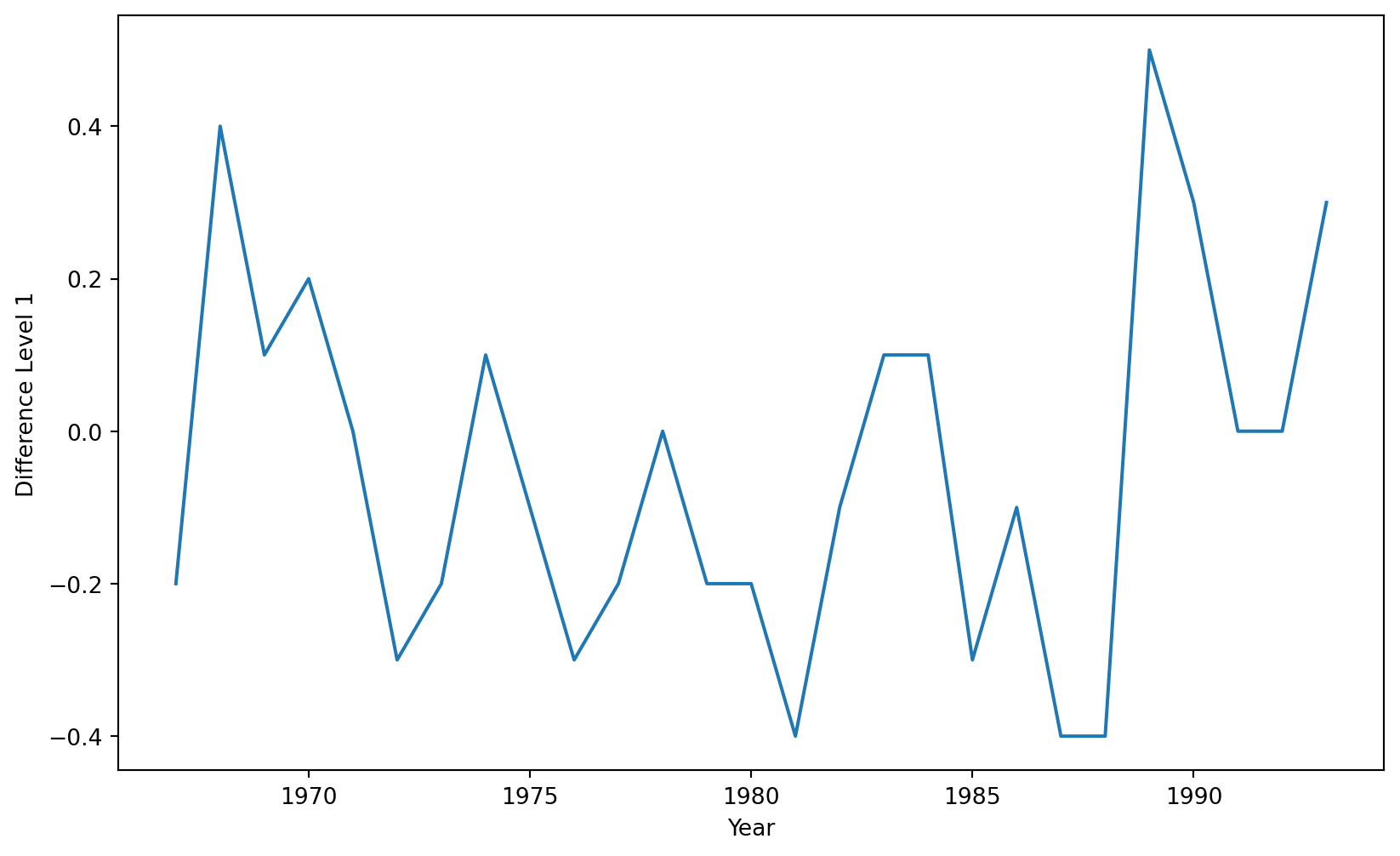

In statsmodels, we apply the integration operator using the pre-loaded diff() function. The function’s k_diff argument specifies the order or level of the operator.

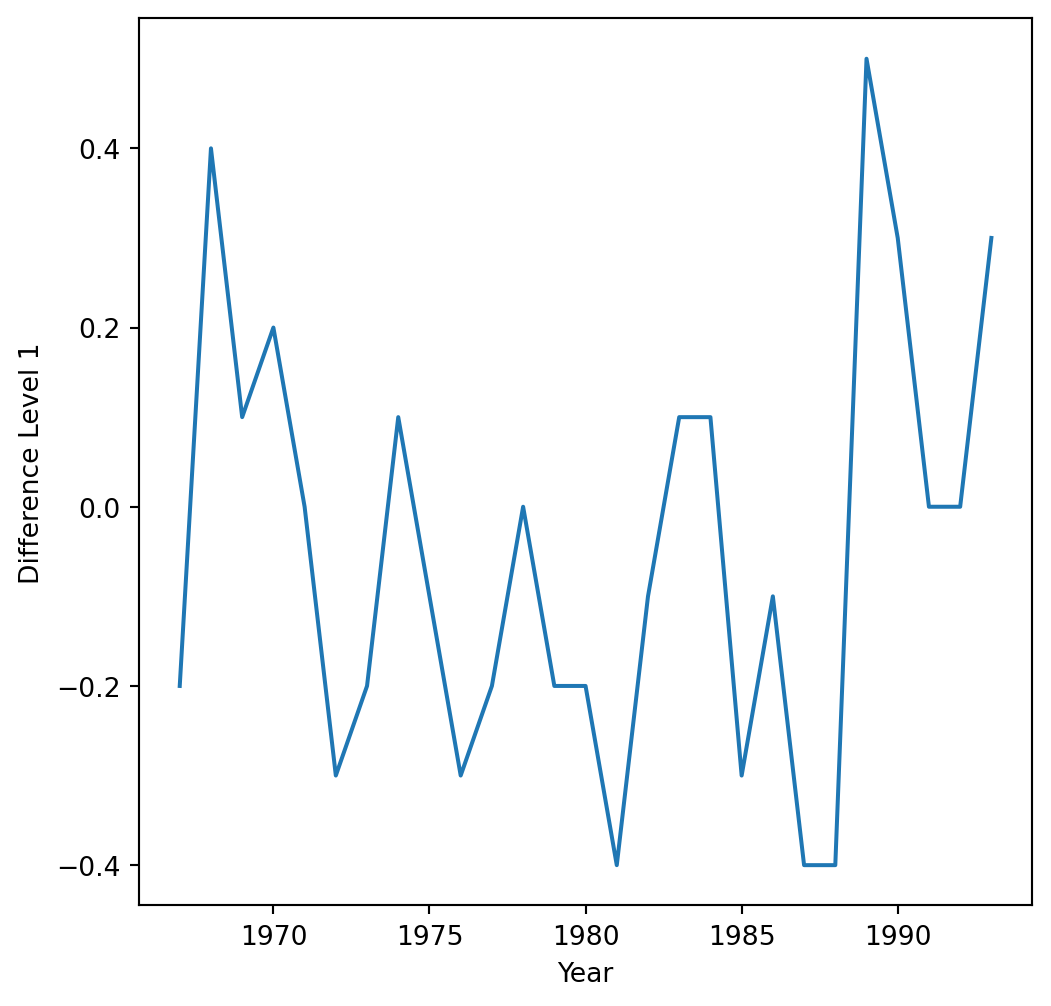

First, let’s use a level-1 operator.

The time series with a level-1 operator looks like this.

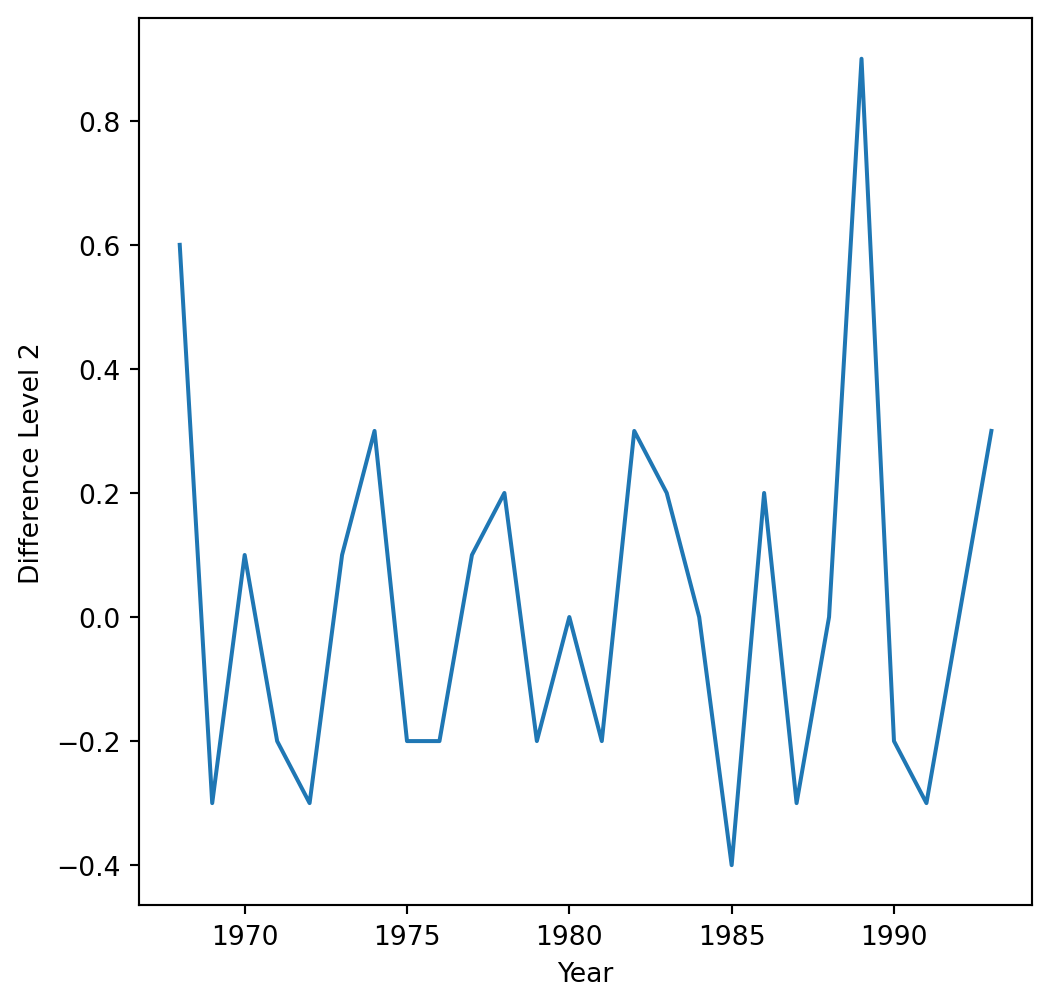

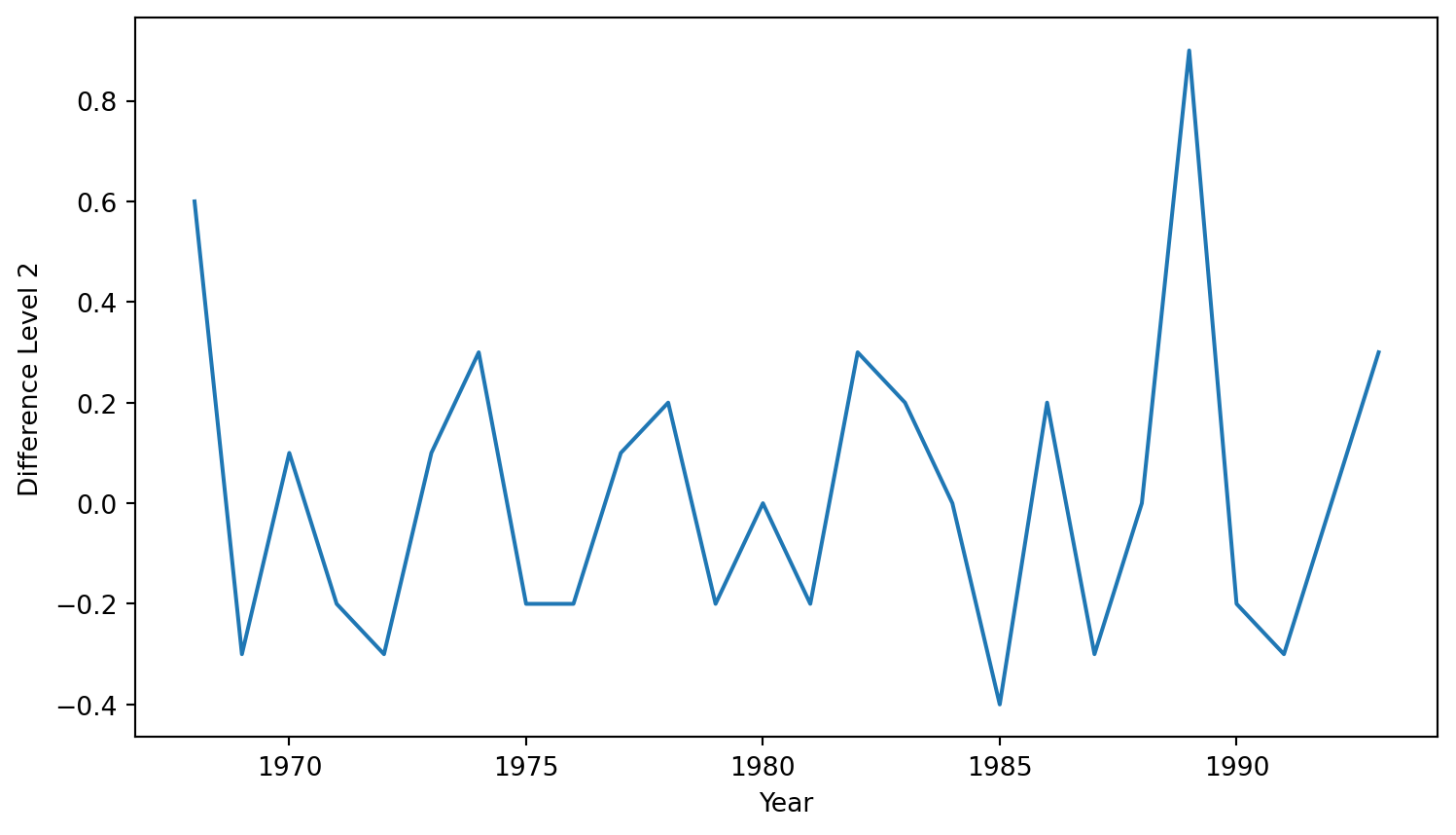

A level-2 operator would work like this.

We see that the level 2 operator is more successful in removing the trend from the original time series.

How do we determine the operator level?

Visualizing the time series and determining whether there is a linear or quadratic trend.

If level 1 and level 2 operators yield similar results, we choose level 1 because it is simpler.

Once this is done, we set our transformed variable \(Z_t\) as the new response variable!

2. Autoregressive (AR) terms

Here we use autoregressive models, but with the new response variable \(Z_t\).

We can have different levels of order (or number of terms) in the autoregression model. For example:

Order 1 model: \(\hat{Z}_t = \hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\beta}_1 Z_{t-1}\).

Order 2 model: \(\hat{Z}_t = \hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\beta}_1 Z_{t-1} + \hat{\beta}_2 Z_{t-2}\).

If necessary, we can exclude the constant coefficient \(\hat{\beta}_0\) from the model.

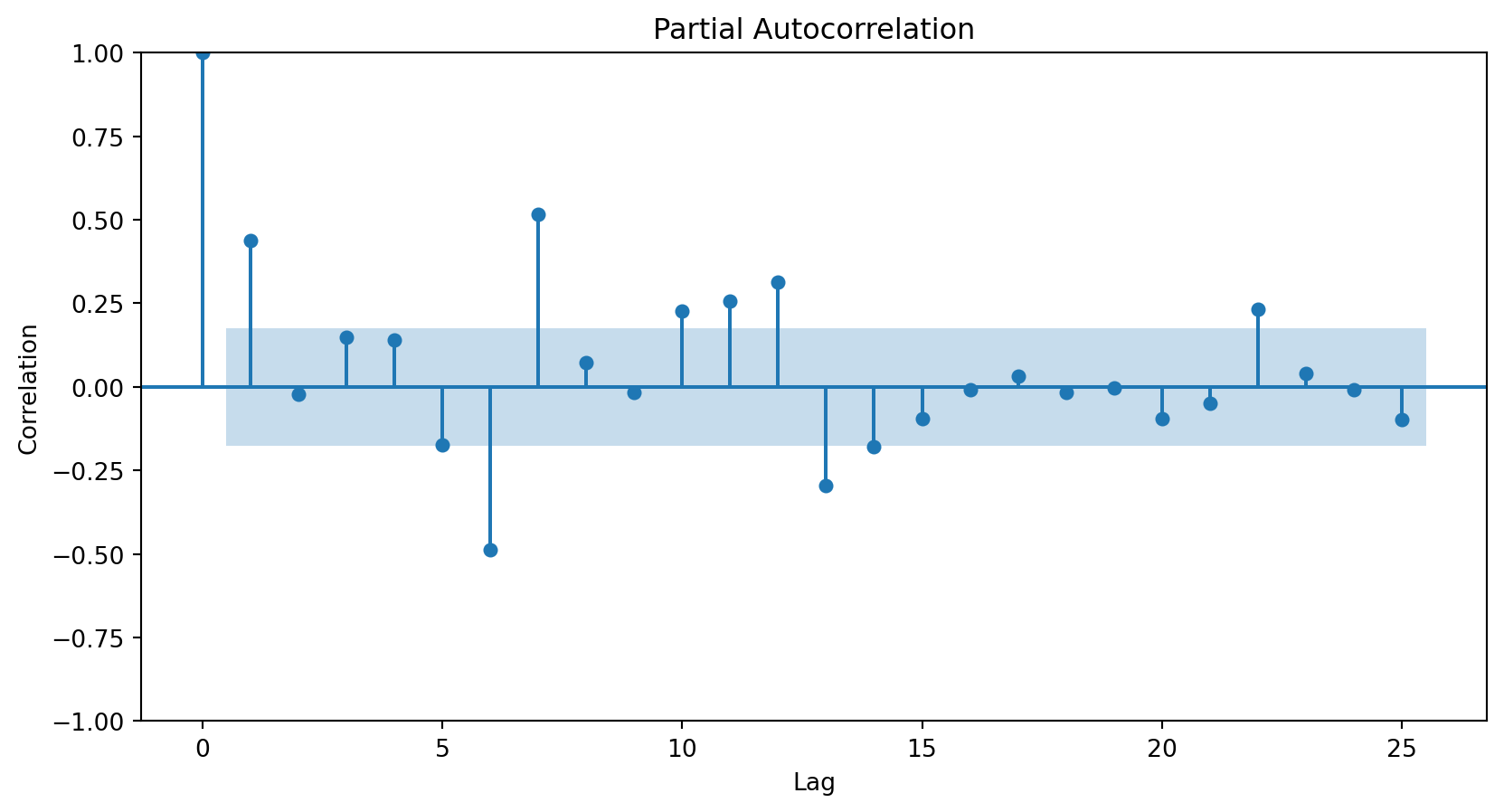

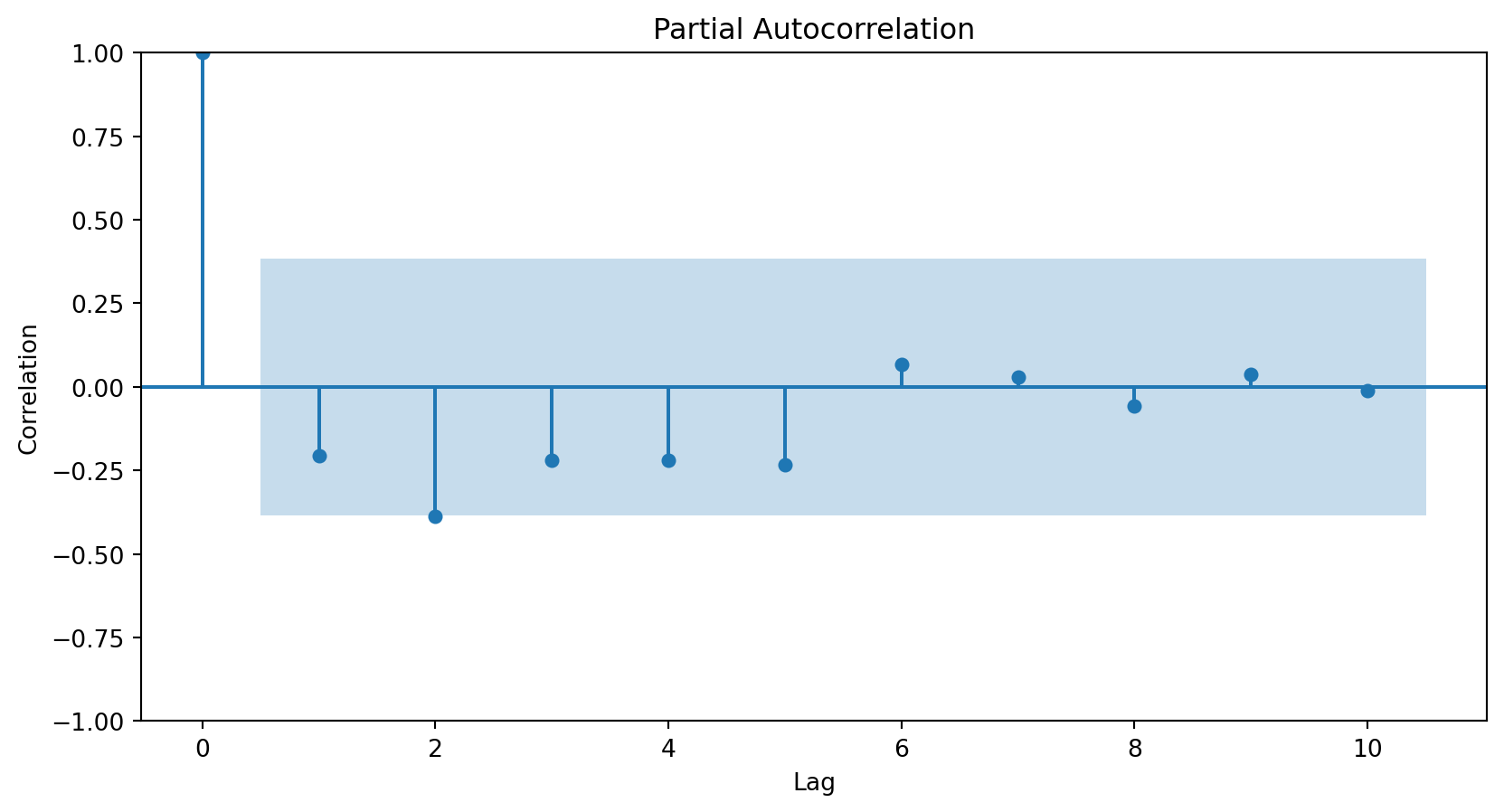

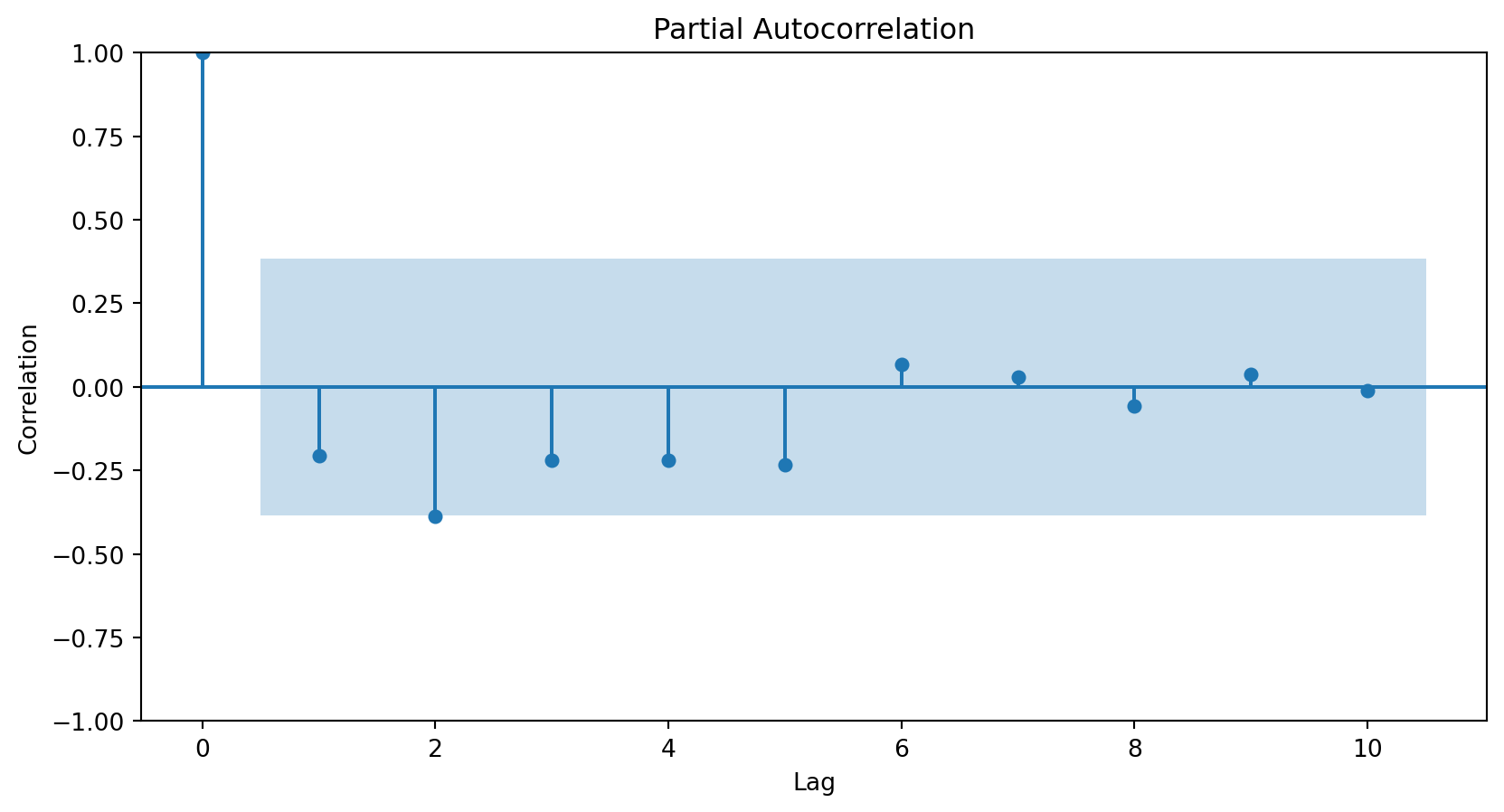

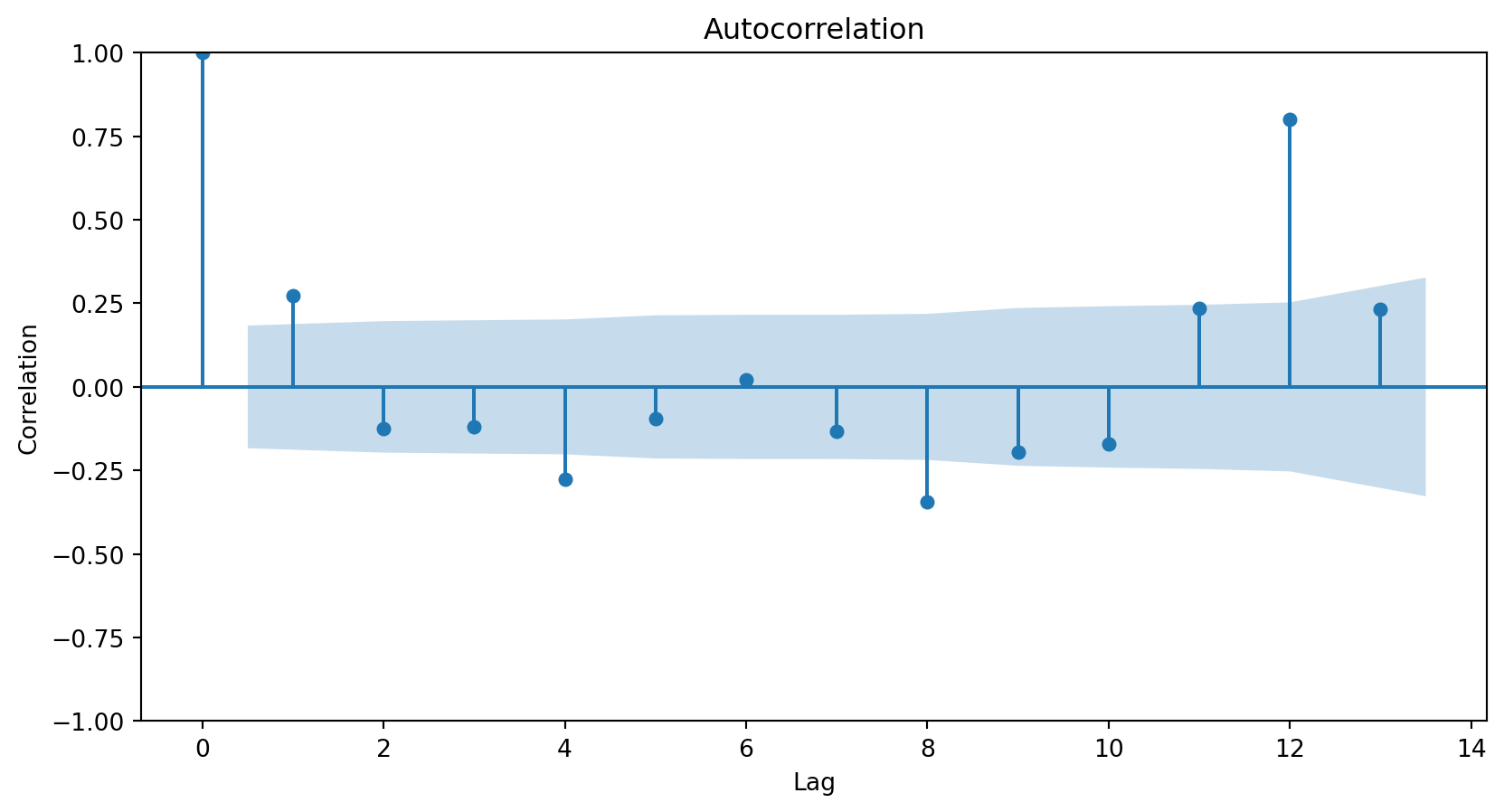

How do we determine the number of terms?

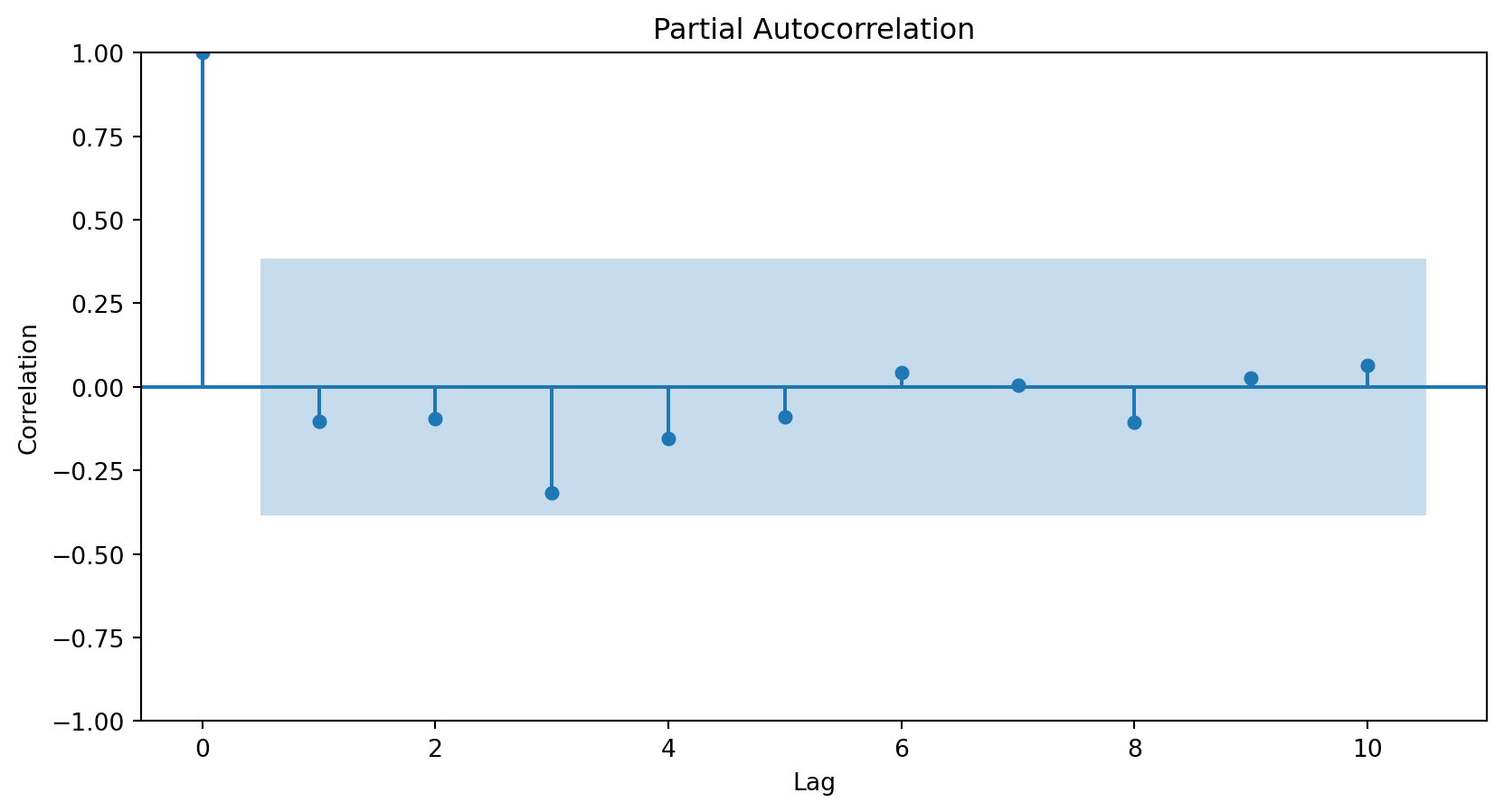

Using the partial autocorrelation function (PACF) of the differenced series.

A first-order autoregressive model has a PACF with a single peak at the first period difference (lag).

A second-order autoregressive model has a PACF with two peaks at the first lags.

In general, the lag at which the PACF cuts off from the confidence limits in the software is the indicated number of AR terms.

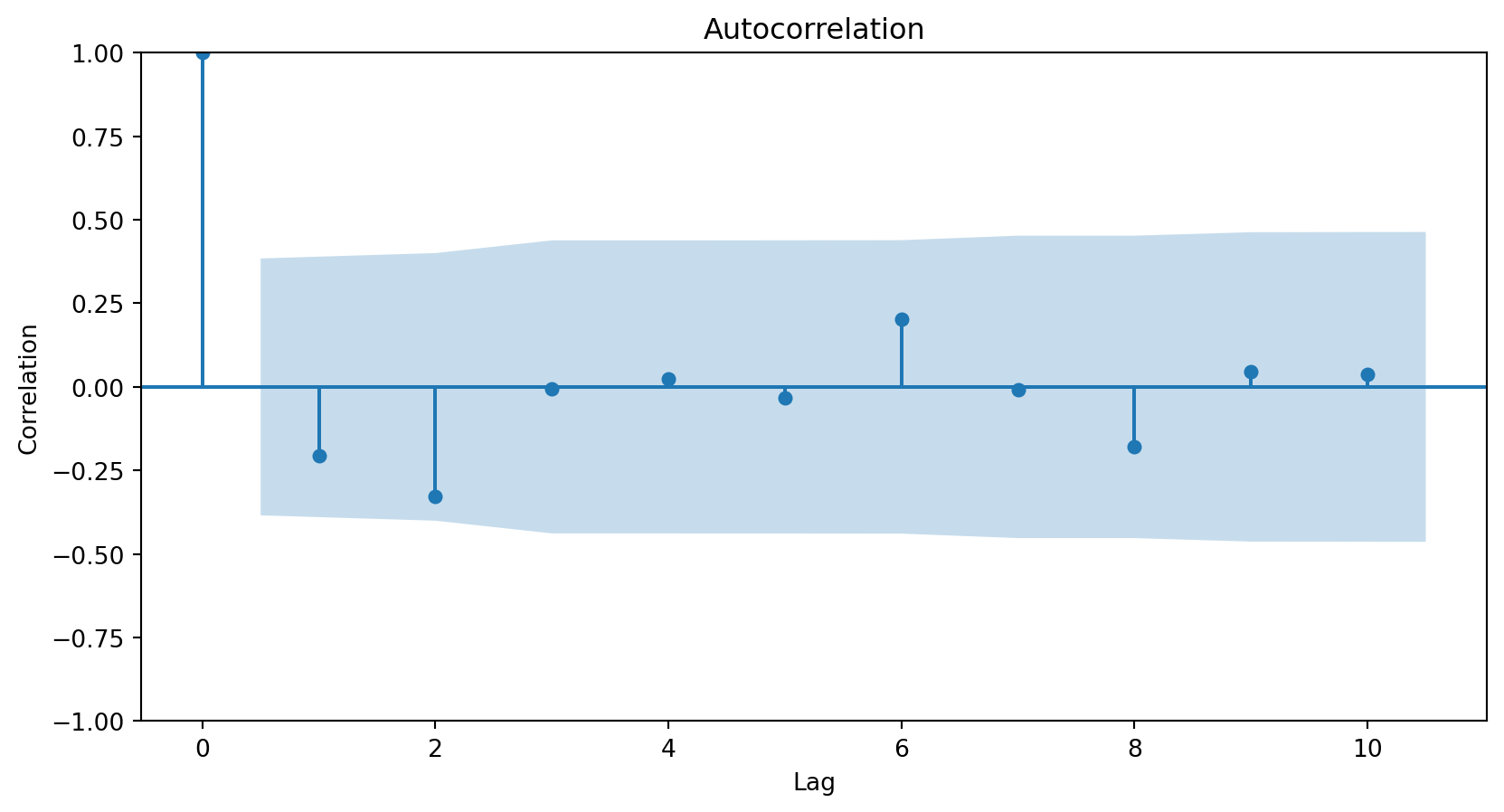

<Figure size 288x288 with 0 Axes>

Using the PACF, we conclude that an autoregressive term of order 2 will be sufficient to capture the relationships between the elements of the series.

<Figure size 288x288 with 0 Axes>

3. Stochastic Terms (Moving Averages, MA)

Instead of using past values of the response variable, a moving average model uses stochastic terms to predict the current response. The model has different versions depending on the number of errors used to predict the response. For example:

- MA of order 1: \(Z_t = \theta_0 + \theta_1 a_{t-1}\);

- MA of order 2: \(Z_t = \theta_0 + \theta_1 a_{t-1} + \theta_2 a_{t-2}\),

where \(\theta_0\) is a constant and \(a_t\) are terms from a white noise series (i.e., random terms).

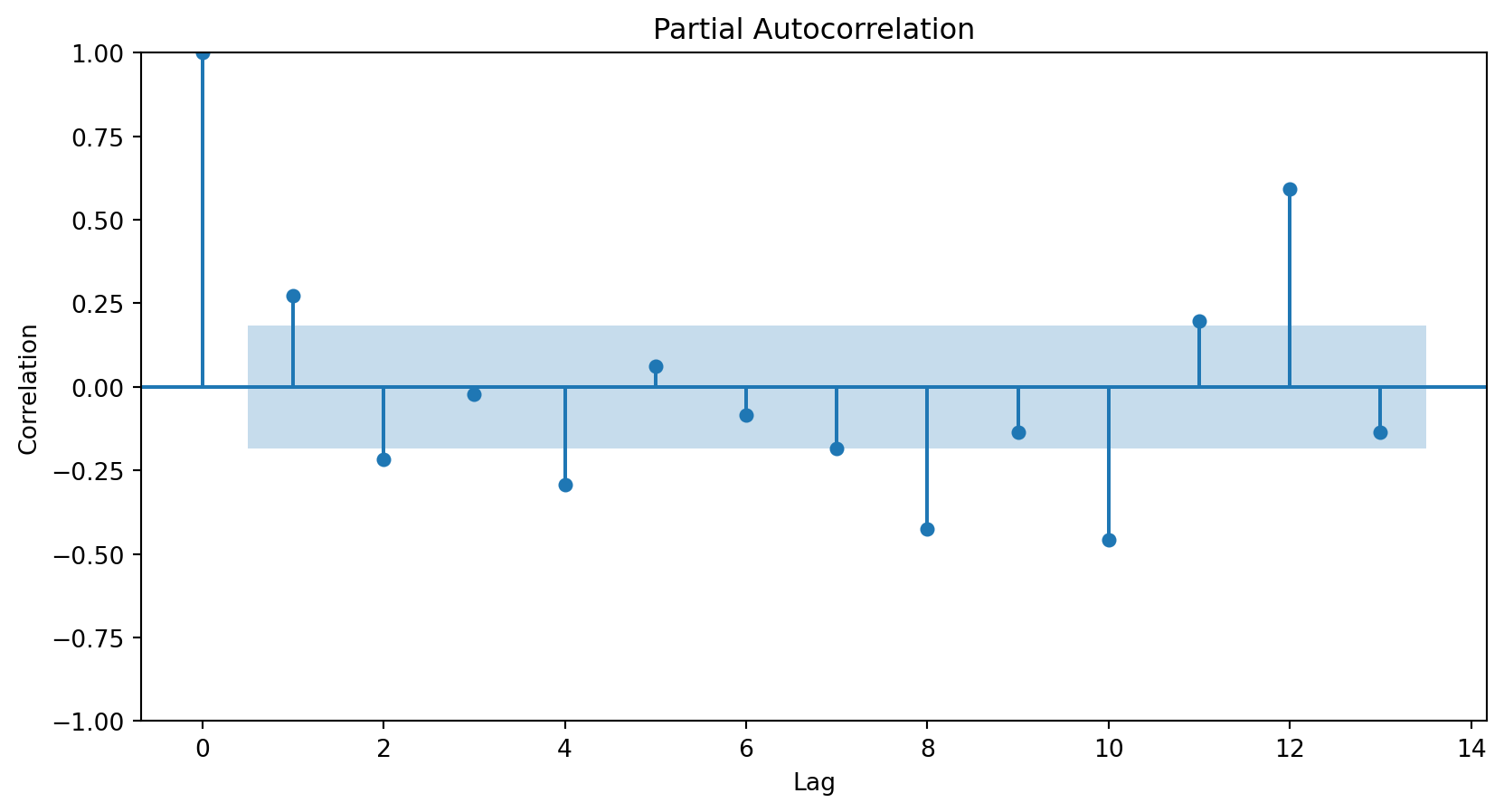

How do I choose the order of the MAs?

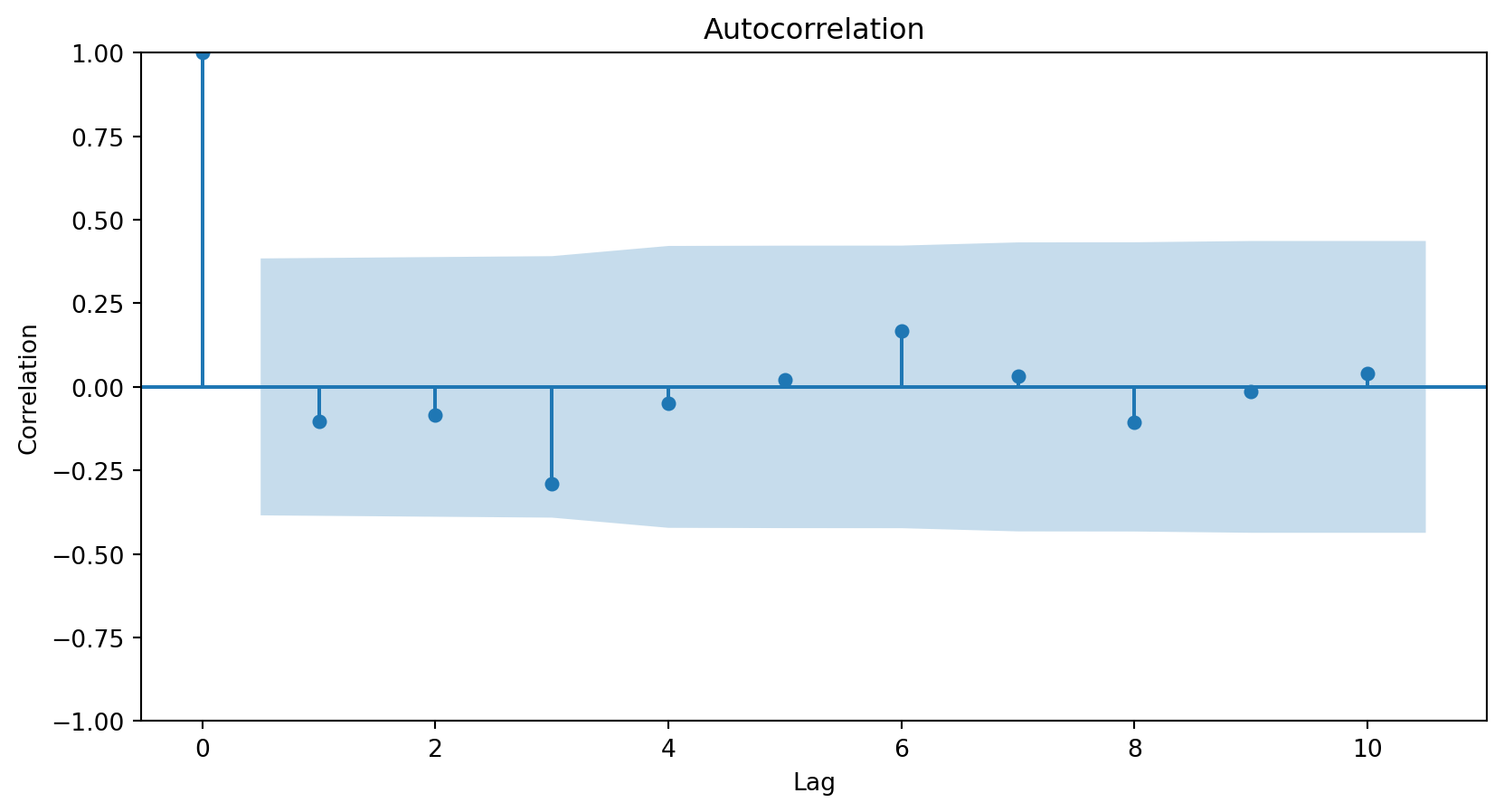

Using the autocorrelation function (ACF) of the differenced series.

- In general, the lag at which the ACF cuts off from the confidence limits in the software is the indicated number of MA terms.

Since there is no significant correlation for any lag above 0, we do not need any MA elements to model the series.

<Figure size 288x288 with 0 Axes>

ARIMA

Define the response differentiation level and create \(Z_t\).

Define the order of the AR model (e.g., order 2).

Define the order of the MA model (e.g., order 1).

\[\hat{Z}_t = \hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\beta}_1 Z_{t-1} + \hat{\beta}_2 Z_{t-2} + \theta_1 a_{t-1}\]

The ARIMA model coefficients are estimated using an advanced method that takes into account the dependencies between the time series responses.

ARIMA in Pyhon

To fit an ARIMA model, we use the ARIMA() function from statsmodels.

The function has an important argument called order, which equals (p,d,q), where

pis the order of the autoregressive model.dis the level of the integration or differencing operator.qis the number of elements in the moving average.

From our previous analysis of the training data for the Canadian workhours example, we conclude that:

We must use a level-2 differencing operator to remove the quadratic trend from the series. Therefore,

d = 2.One autoregressive term should be sufficient to capture the patterns in the time series. Therefore,

p = 2.It is not necessary to have moving average terms. Therefore,

q = 0.

Once this is defined, we can train an ARIMA model using the training data with the following code:

Technically, ARIMA() defines the model and .fit() fits the model to the data using maximum likelihood estimation.

After fitting, we can get a summary of the model fit using the following code.

SARIMAX Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: Hours per Week No. Observations: 28

Model: ARIMA(2, 2, 0) Log Likelihood -2.537

Date: Thu, 04 Sep 2025 AIC 11.074

Time: 10:16:52 BIC 14.849

Sample: 0 HQIC 12.161

- 28

Covariance Type: opg

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ar.L1 -0.3236 0.403 -0.803 0.422 -1.113 0.466

ar.L2 -0.4401 0.250 -1.760 0.078 -0.930 0.050

sigma2 0.0699 0.021 3.356 0.001 0.029 0.111

===================================================================================

Ljung-Box (L1) (Q): 0.26 Jarque-Bera (JB): 3.02

Prob(Q): 0.61 Prob(JB): 0.22

Heteroskedasticity (H): 1.48 Skew: 0.74

Prob(H) (two-sided): 0.57 Kurtosis: 3.75

===================================================================================

Warnings:

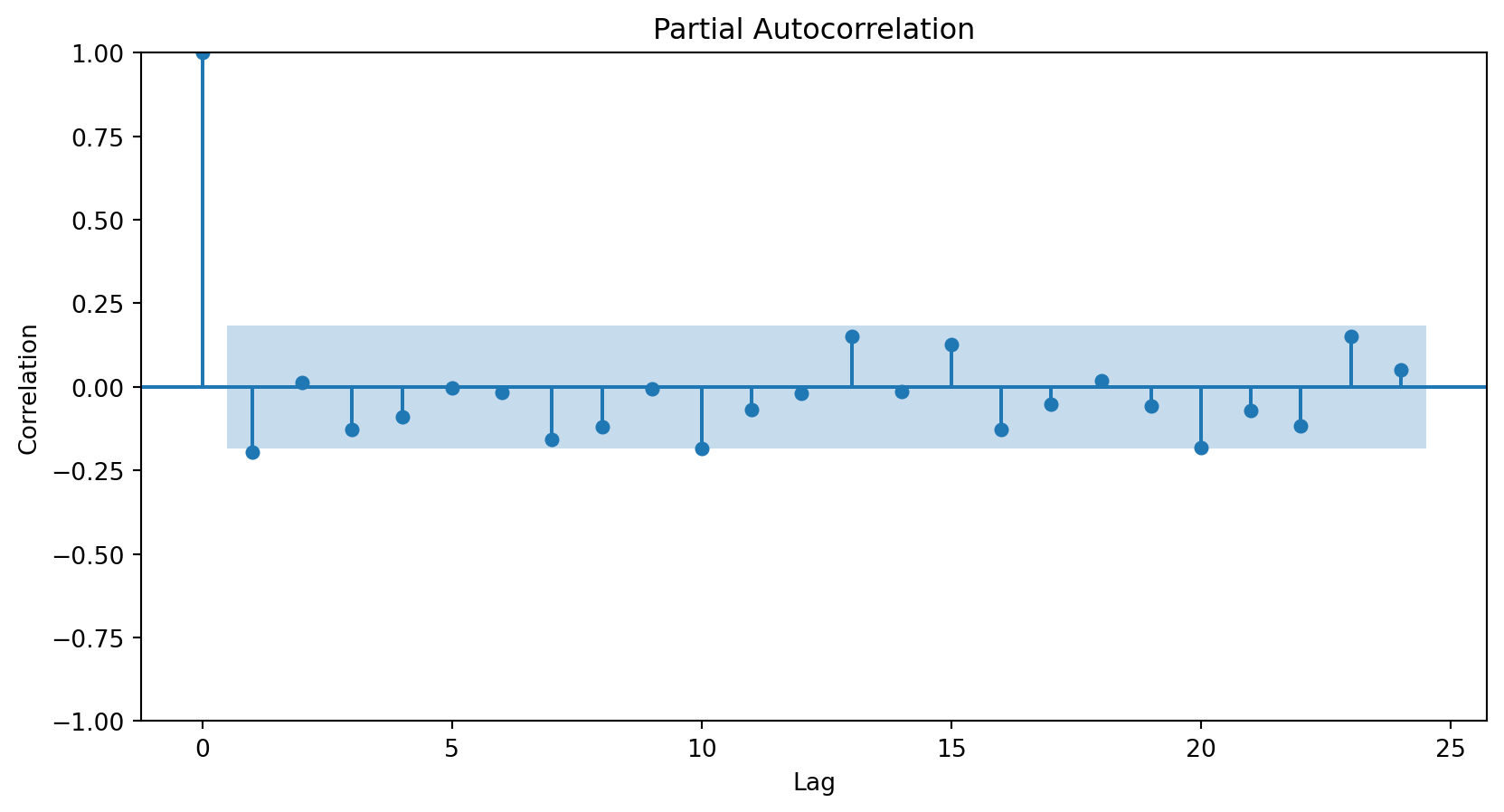

[1] Covariance matrix calculated using the outer product of gradients (complex-step).The next step in evaluating an ARIMA model is to study the model’s residuals to ensure there is nothing else to explain in the model.

However, since the ARIMA model has two AR terms, we must inspect the residuals starting from the third observation. We achieve this using the code below.

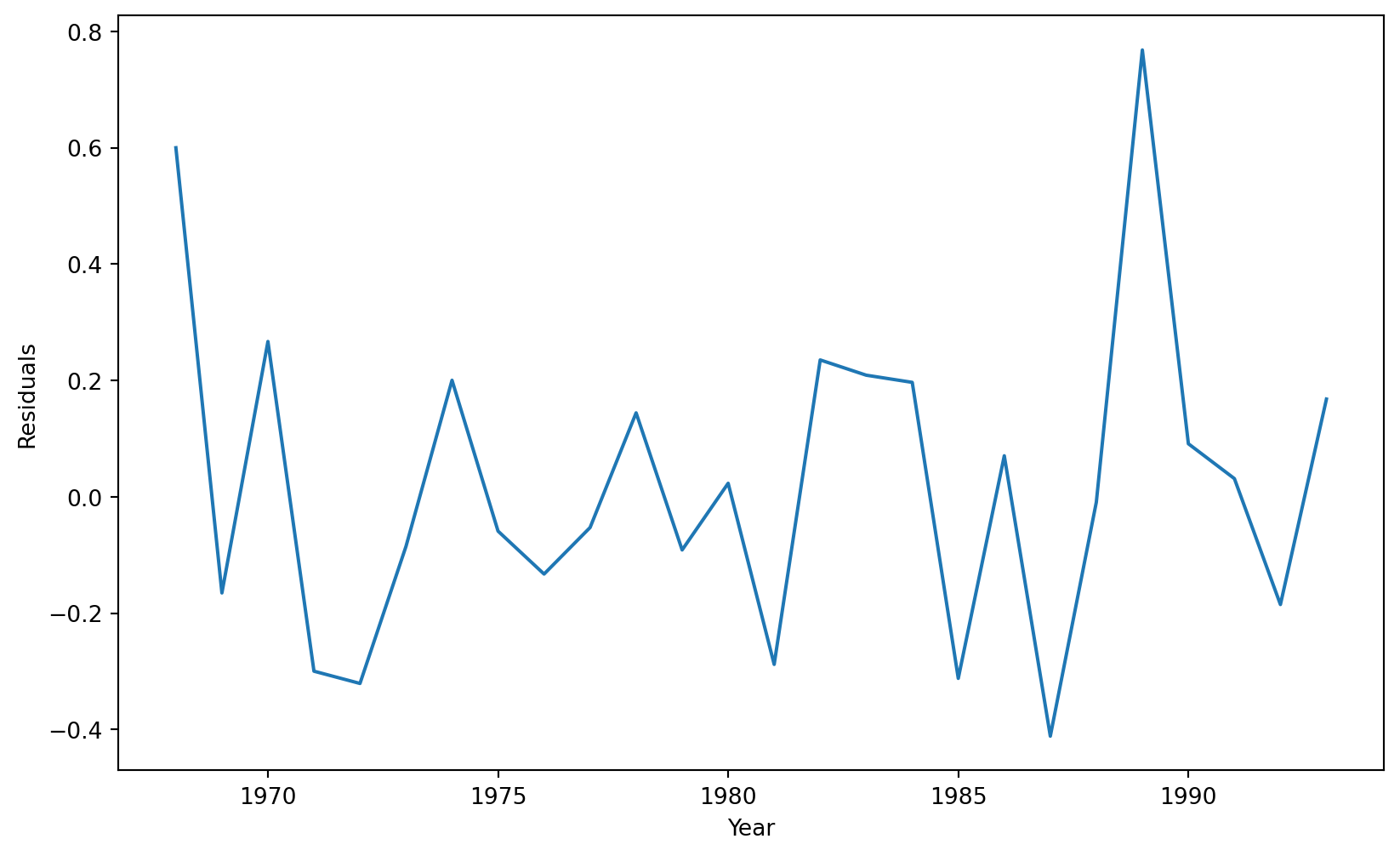

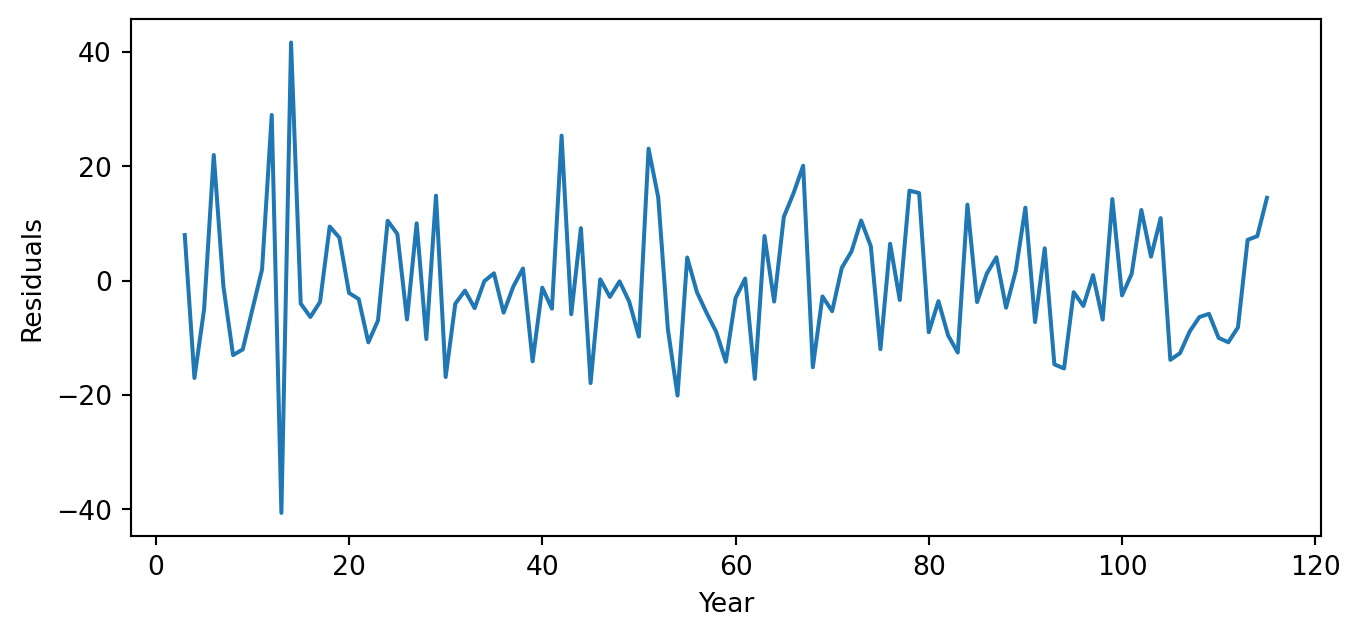

Time series of residuals

Correlation plots

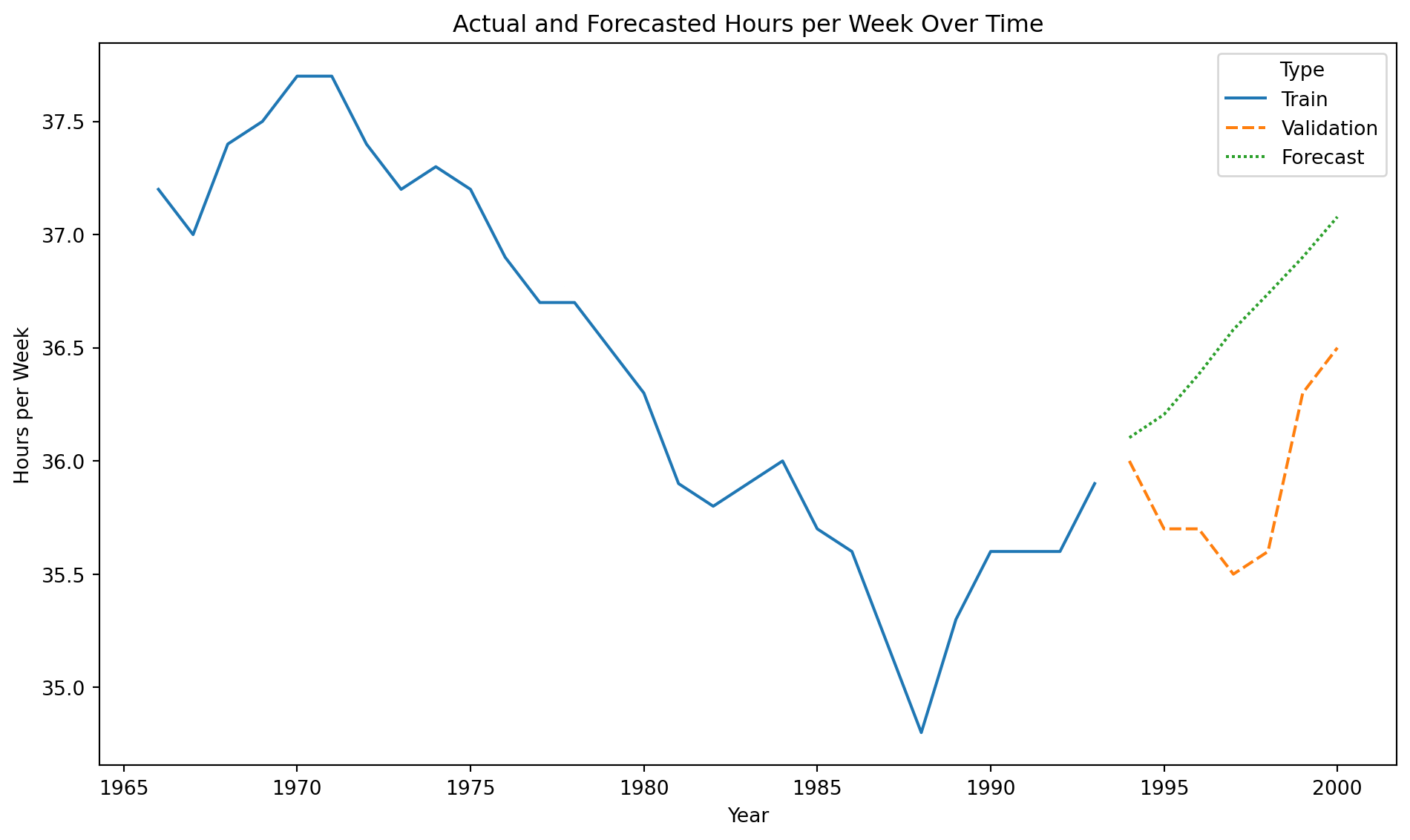

The three graphs show no obvious patterns or significant correlations between the residuals. Therefore, we say the model is good.

Forecast

Once the model is validated, we make predictions for elements in the time series.

To predict the average number of hours worked in the next, say, 3 years, we use the .forecast() function. The steps argument indicates the number of steps in the future to make the predictions.

Model evaluation using RMSE

Instead of evaluating the ARIMA model using graphical analyses of the residuals, we can take a more data-driven approach and evaluate the model using the root mean squared error (RMSE).

To this end, we use the

mean_squared_error()function with the validation responses and our predictions. We take the square root of the result to obtain the RMSE.

Validation data

The validation data has 7 time periods that can be determined using the command below.

So, we must forecast 7 periods ahead using our ARIMA model.

Using the forecast and validation data, we compute the RMSE.

Naive forecast

To determine if the RMSE is high or small, we must compare it with a naive forecast that predicts the response \(Y_t\) with the previous one \(Y_{t-1}\). To build this forecast, we follow three steps.

First, we shift the time series in the validation data by one position using the .shit(1) function.

Second, we notice that the first element of the shifted series is missing or not available (NaN). We thus fill it in with the last observation in our training dataset, which we can obtain using the .iloc() function.

Third, we input 35.9 as the first record in naive_forecast. The first record of the object is indexed by a 28.

Our naive forecast of the time series in the validation data would be these one:

| Naive Forecast | Hours per week | |

|---|---|---|

| 28 | 35.9 | 36.0 |

| 29 | 36.0 | 35.7 |

| 30 | 35.7 | 35.7 |

| 31 | 35.7 | 35.5 |

| 32 | 35.5 | 35.6 |

| 33 | 35.6 | 36.3 |

| 34 | 36.3 | 36.5 |

The RMSE of the naive forecast is calculated below.

naive_rmse = mean_squared_error(Canadian_validation["Hours per Week"],

naive_forecast)

print(round(naive_rmse**(1/2), 2))0.31We conclude that predicting with the previous response is a better approach than predicting with an ARIMA model. This is because the RMSE for the naive forecast is 0.31, and that of the ARIMA model is 0.75.

The SARIMA Model

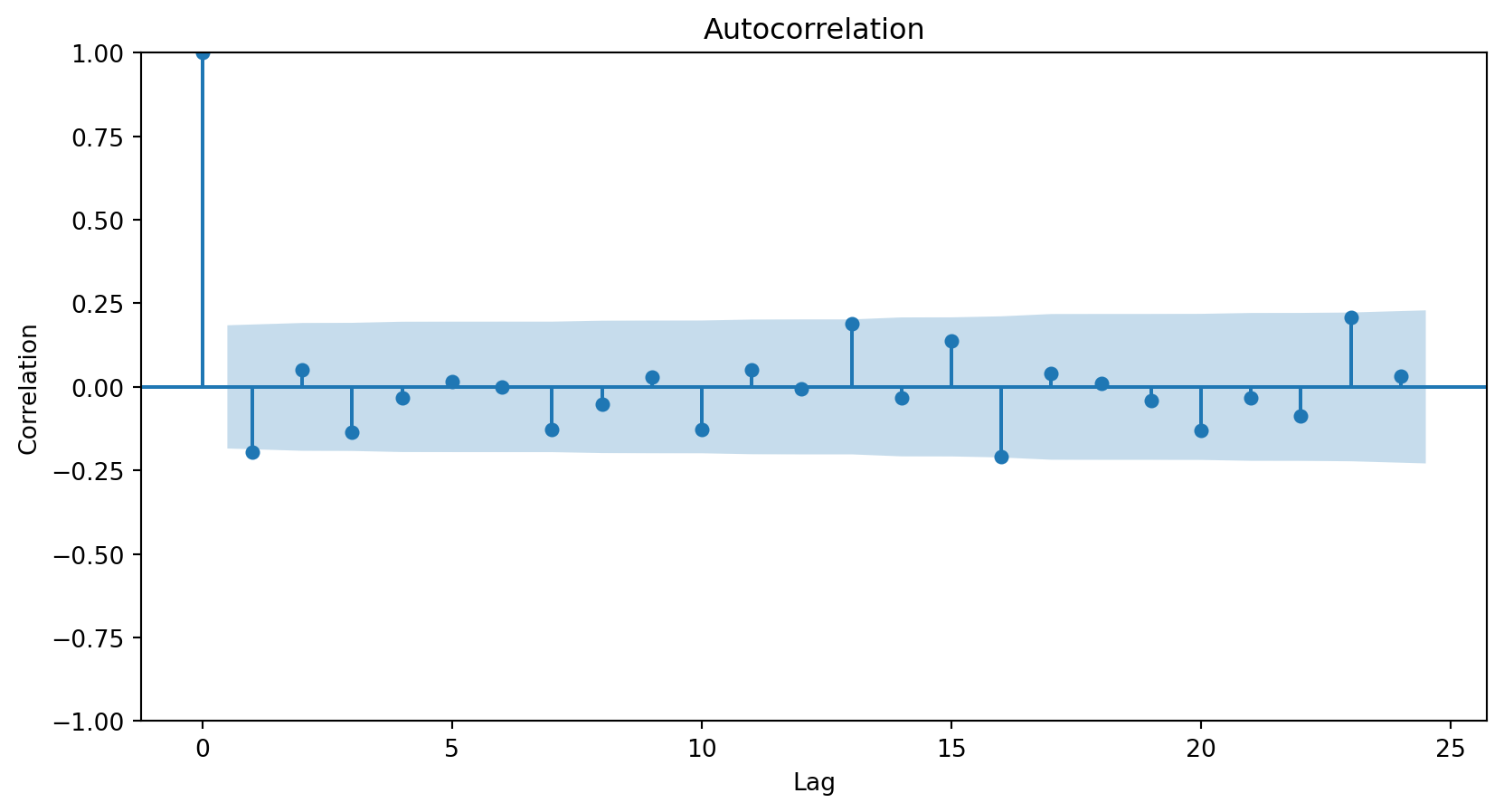

Seasonality

Seasonality consists of repetitive or cyclical behavior that occurs with a constant frequency.

It can be identified from the series graph or using the ACF and PACF.

To do this, we must have removed the trend.

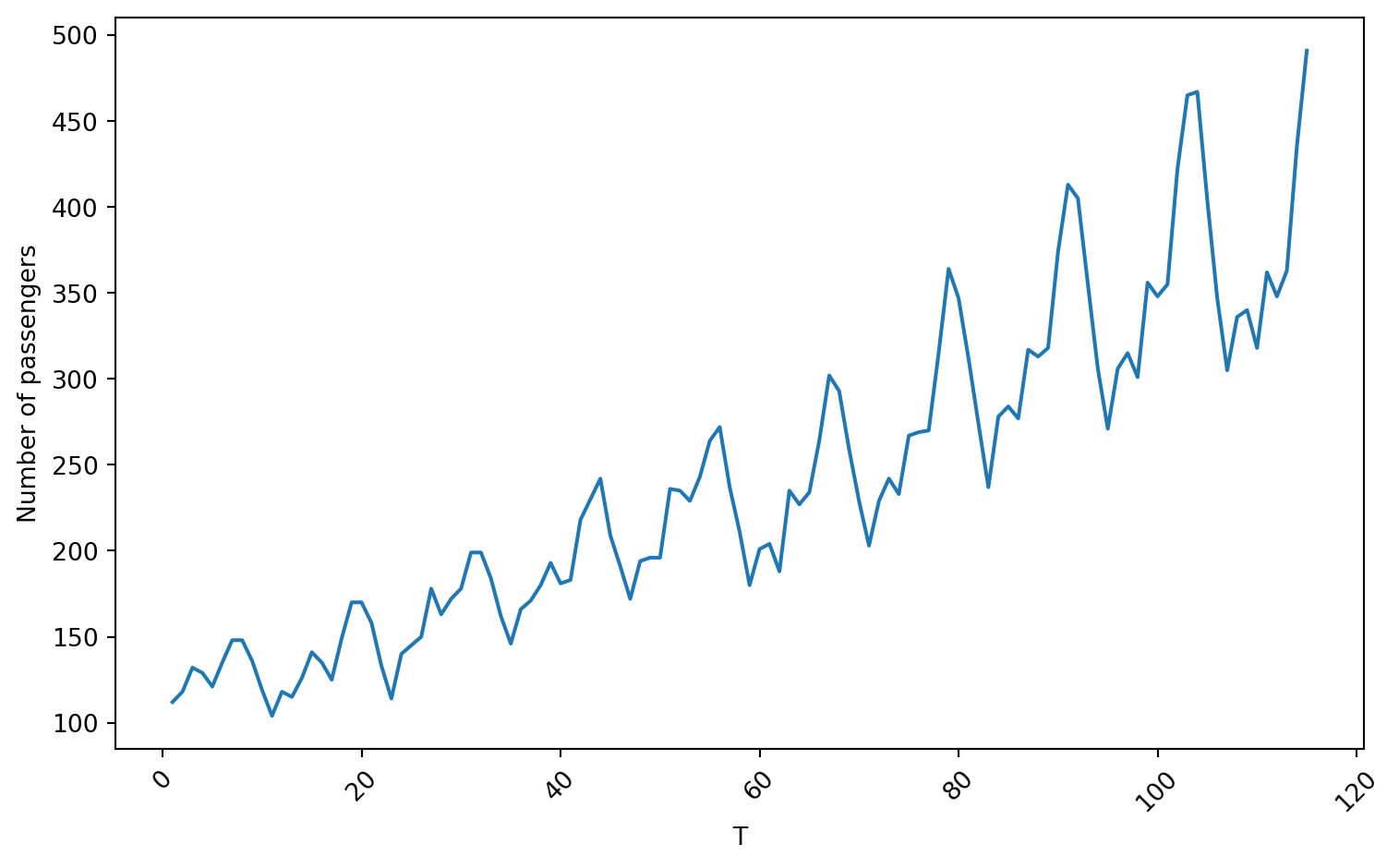

Example 3

We use the Airline data containing the number of passengers of an international airline per month between 1949 and 1960.

Create training and validation data

We use 80% of the time series for training and the rest for validation.

Training data

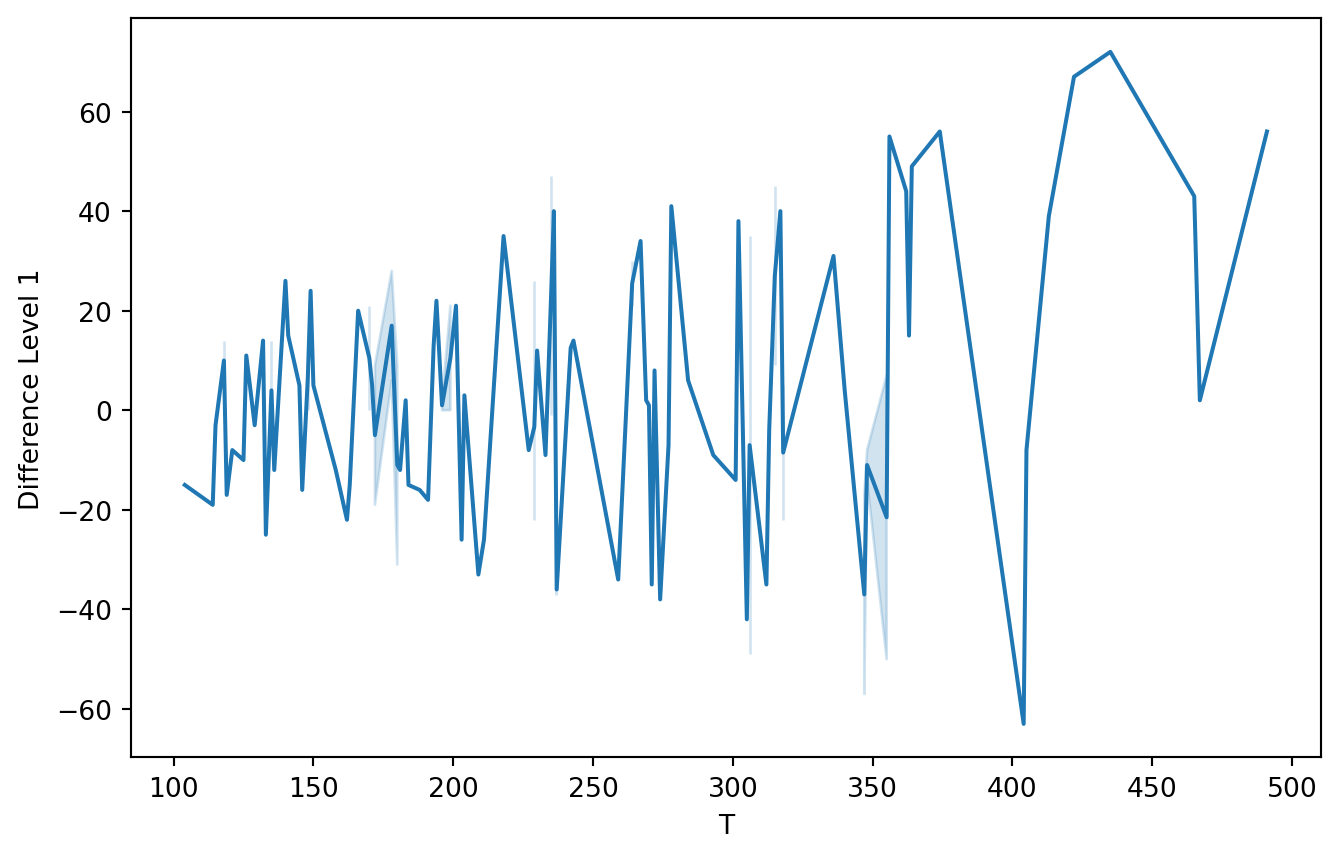

First, let’s use a level-1 operator.

Autocorrelation plots

<Figure size 288x288 with 0 Axes>

<Figure size 288x288 with 0 Axes>

SARIMA model

The SARIMA (Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) model is an extension of the ARIMA model for modeling seasonality patterns.

The SARIMA model has three additional elements for modeling seasonality in time series.

- Differenced or integrated operators (integrated) for seasonality.

- Autoregressive terms (autoregressive) for seasonality.

- Stochastic terms or moving averages (moving average) for seasonality.

Notation

Seasonality in a time series is a regular pattern of change that repeats over \(S\) time periods, where \(S\) defines the number of time periods until the pattern repeats again.

For example, there is seasonality in monthly data, where high values always tend to occur in some particular months and low values always tend to occur in other particular months.

In this case, \(S=12\) (months per year) is the length of periodic seasonal behavior. For quarterly data, \(S=4\) time periods per year.

Seasonal differentiation

This is the difference between a response and a response with a lag that is a multiple of \(S\).

For example, with monthly data \(S=12\),

- A level 1 seasonal difference is \(Y_{t} - Y_{t-12}\).

- A level 2 seasonal difference is \((Y_{t-12}) - (Y_{t-12} - Y_{t-24})\).

Seasonal differencing eliminates the seasonal trend and can also eliminate a type of nonstationarity caused by a seasonal random walk.

Seasonal AR and MA Terms

In SARIMA, the seasonal AR and MA component terms predict the current response (\(Y_t\)) using responses and errors at times with lags that are multiples of \(S\).

For example, with monthly data \(S = 12\),

- The first-order seasonal AR model would use \(Y_{t-12}\) to predict \(Y_{t}\).

- The second-order seasonal AR model would use \(Y_{t-12}\) and \(Y_{t-24}\) to predict \(Y_{t}\).

- The first-order seasonal MA model would use the stochastic term \(a_{t-12}\) as a predictor.

- The second-order seasonal MA model would use the stochastic terms \(a_{t-12}\) and \(a_{t-24}\) as predictors.

To fit the SARIMA model, we use the ARIMA() function from statsmodels, but with an additional argument, seasonal_order=(0, 0, 0, 0).

This is the order (P, D, Q, s) of the seasonal component of the model for the autoregressive parameters, differencing operator levels, moving average parameters, and periodicity.

Let’s fit a SARIMA model.

Summary of fit

SARIMAX Results

=========================================================================================

Dep. Variable: Number of passengers No. Observations: 115

Model: ARIMA(1, 2, 1)x(1, 1, [], 12) Log Likelihood -374.241

Date: Thu, 04 Sep 2025 AIC 756.482

Time: 10:16:53 BIC 766.943

Sample: 0 HQIC 760.717

- 115

Covariance Type: opg

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ar.L1 -0.1729 0.094 -1.833 0.067 -0.358 0.012

ma.L1 -0.9999 14.439 -0.069 0.945 -29.300 27.300

ar.S.L12 -0.1303 0.084 -1.543 0.123 -0.296 0.035

sigma2 91.7900 1326.009 0.069 0.945 -2507.139 2690.719

===================================================================================

Ljung-Box (L1) (Q): 0.00 Jarque-Bera (JB): 3.18

Prob(Q): 0.98 Prob(JB): 0.20

Heteroskedasticity (H): 1.13 Skew: 0.39

Prob(H) (two-sided): 0.73 Kurtosis: 2.64

===================================================================================

Warnings:

[1] Covariance matrix calculated using the outer product of gradients (complex-step).Residual analysis

We can have a graphical evaluation of the model’s performance using a residual analysis.

<Figure size 576x576 with 0 Axes>

<Figure size 576x576 with 0 Axes>

Validation

The validation data has 29 time periods that can be determined using the command below.

So, we must forecast 7 periods ahead using our SARIMA model.

Using the forecast and validation data, we compute the RMSE.

Comparison with a naive forecast

Now, we build a naive forecast to study the performance of our SARIMA model. To this end, we shift the validation data by one period using the code below.

Next, we determine the last element of the training data.

Finally, we assemble our naive forecast by replacing the first entry of naive_forecast with the last entry of the response in the training dataset.

Let’s calculate the RMSE of the naive forecast.

naive_rmse = mean_squared_error(Airline_validation["Number of passengers"], naive_forecast)

print(round(naive_rmse**(1/2), 2))52.49The RMSE of the SARIMA model is 26.38, while that of the naive forecast is 54.15. Therefore, the SARIMA model is better than the naive forecast.

Return to main page

Tecnologico de Monterrey

Comments

The differentiation operator de-trends the time series.