# Importing necessary libraries

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

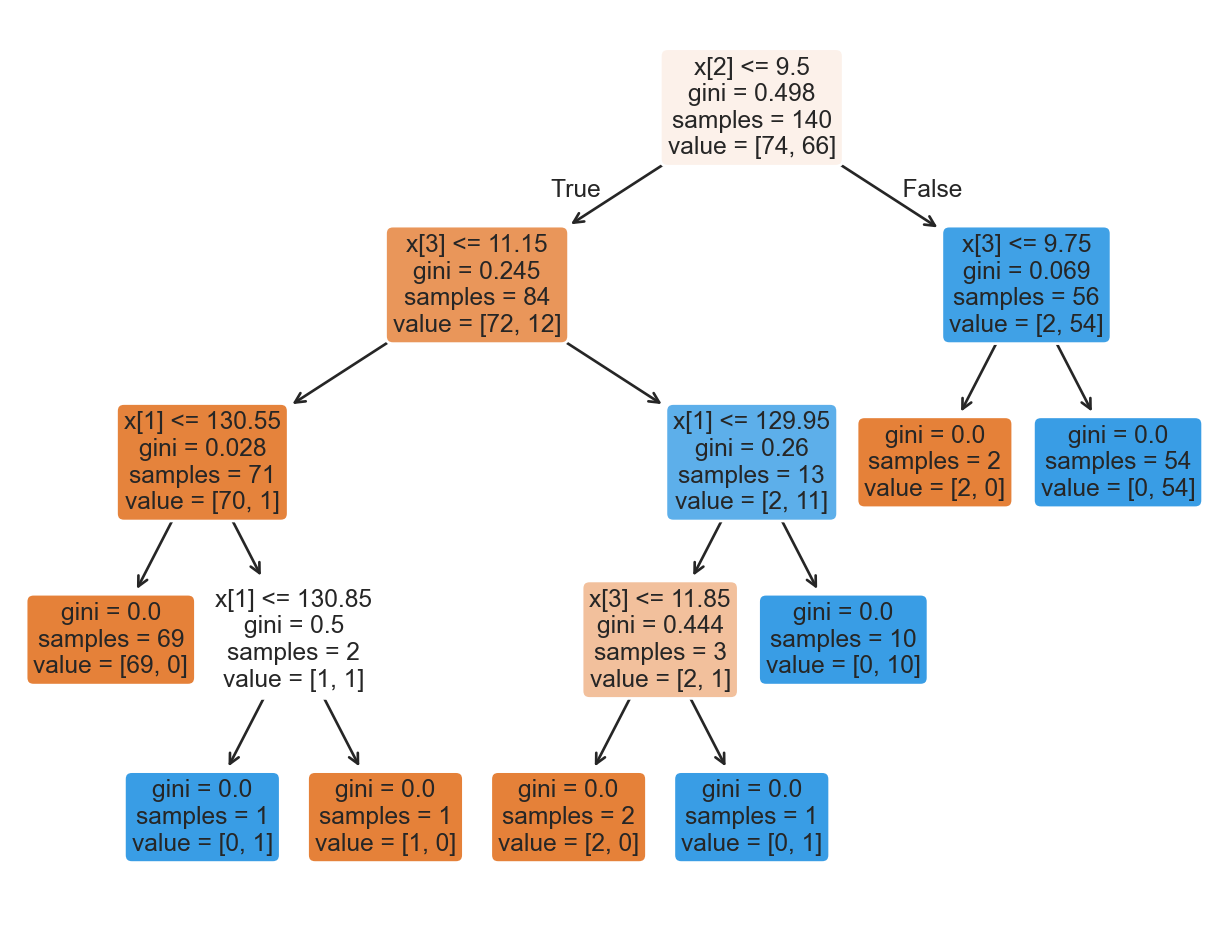

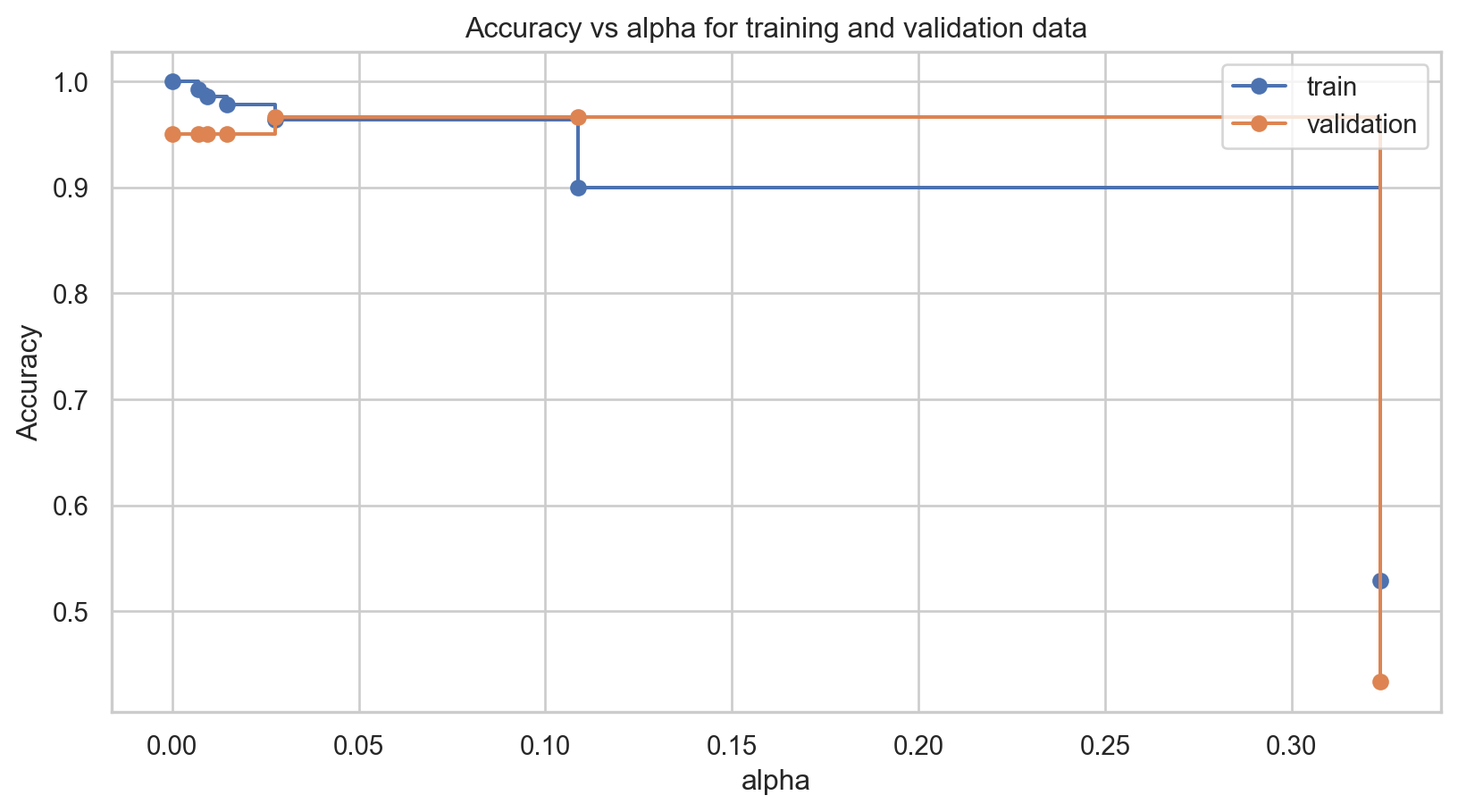

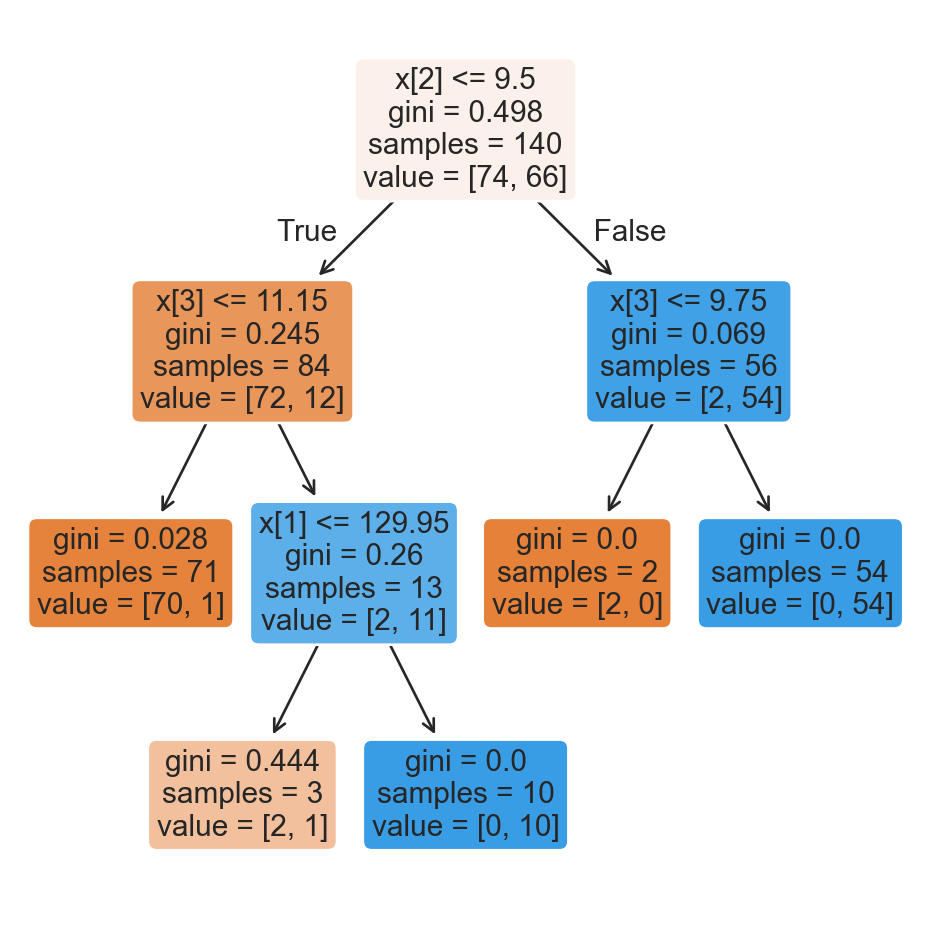

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier, plot_tree

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix, ConfusionMatrixDisplay

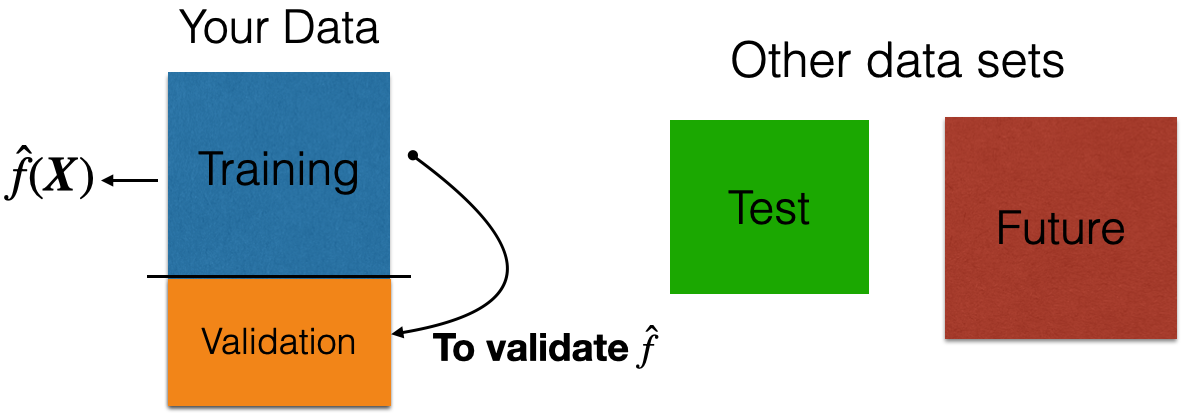

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, recall_score, precision_scoreMain data science problems

Regression Problems. The response is numerical. For example, a person’s income, the value of a house, or a patient’s blood pressure.

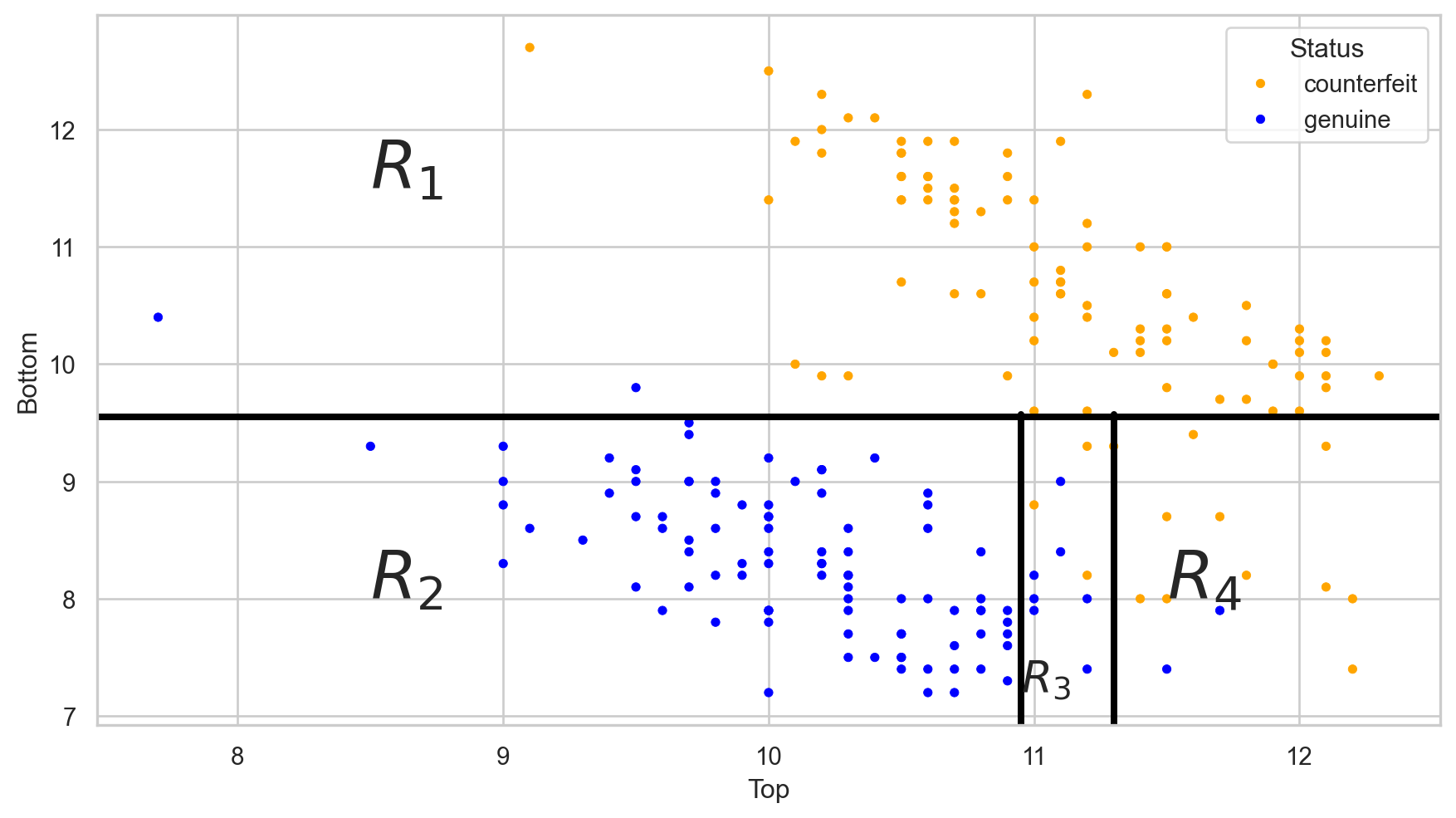

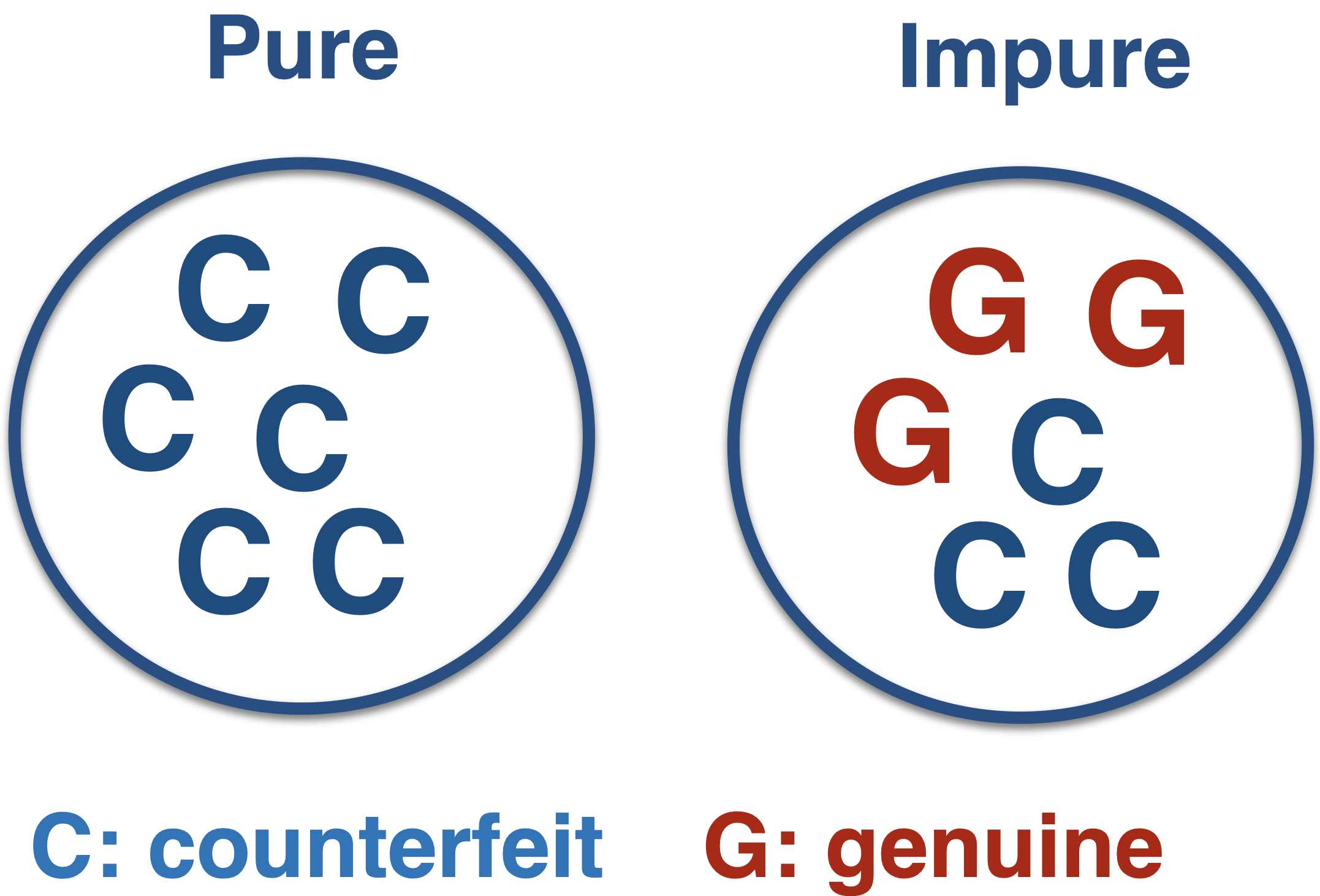

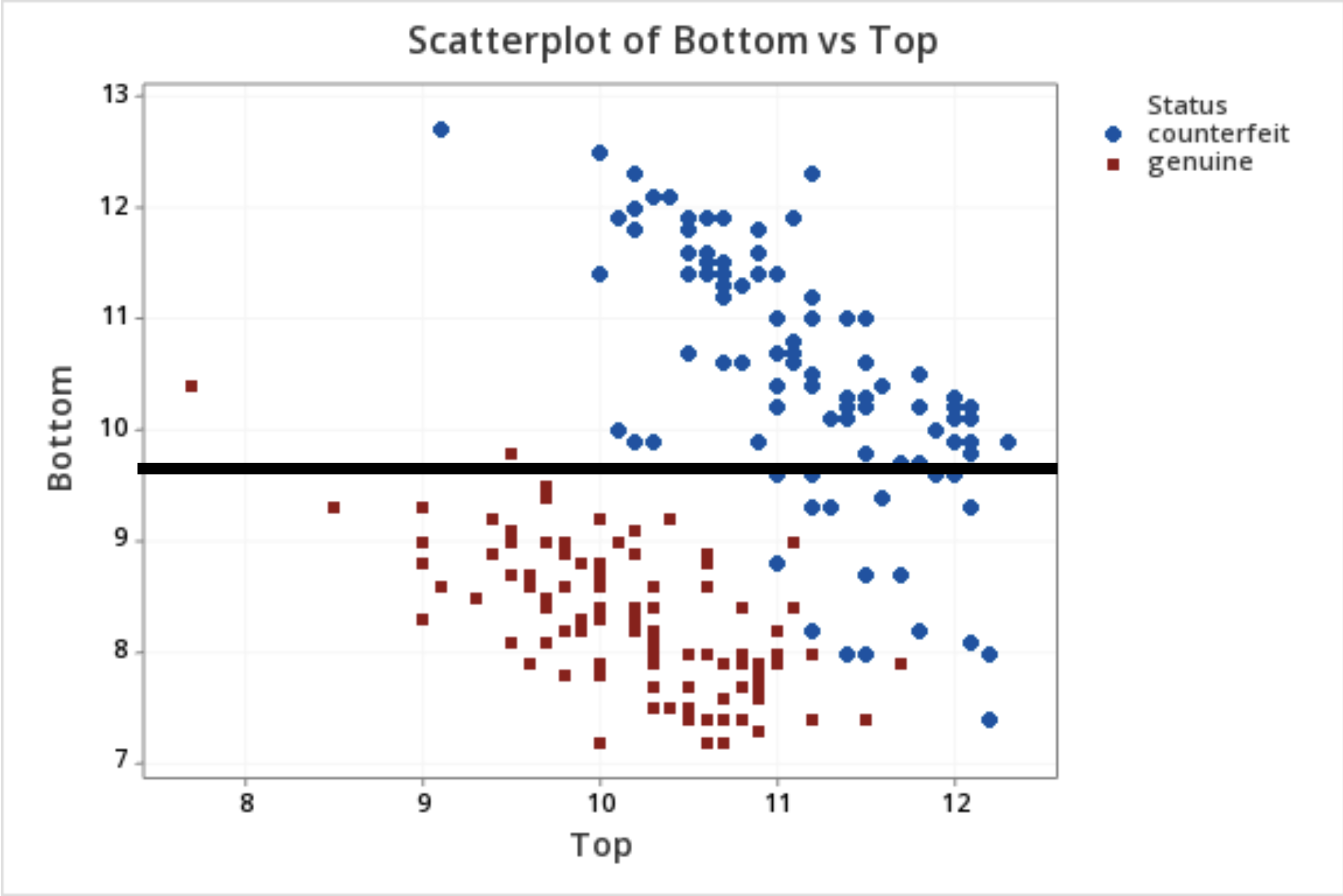

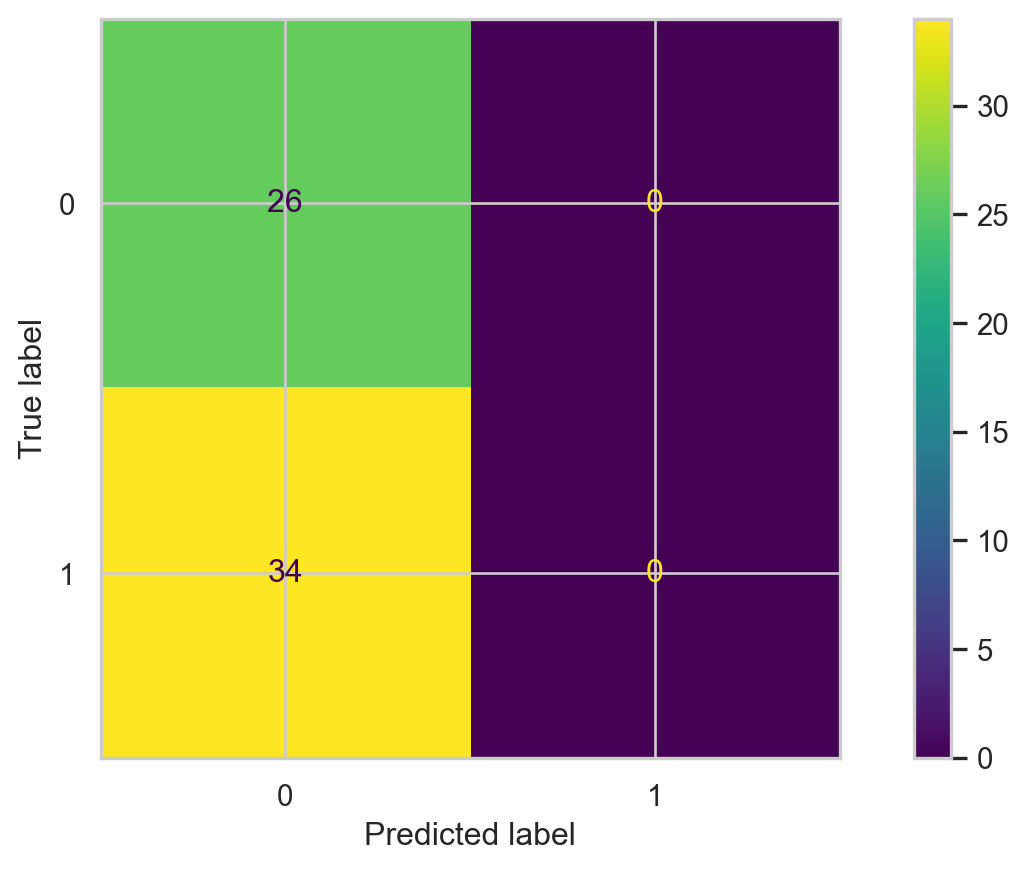

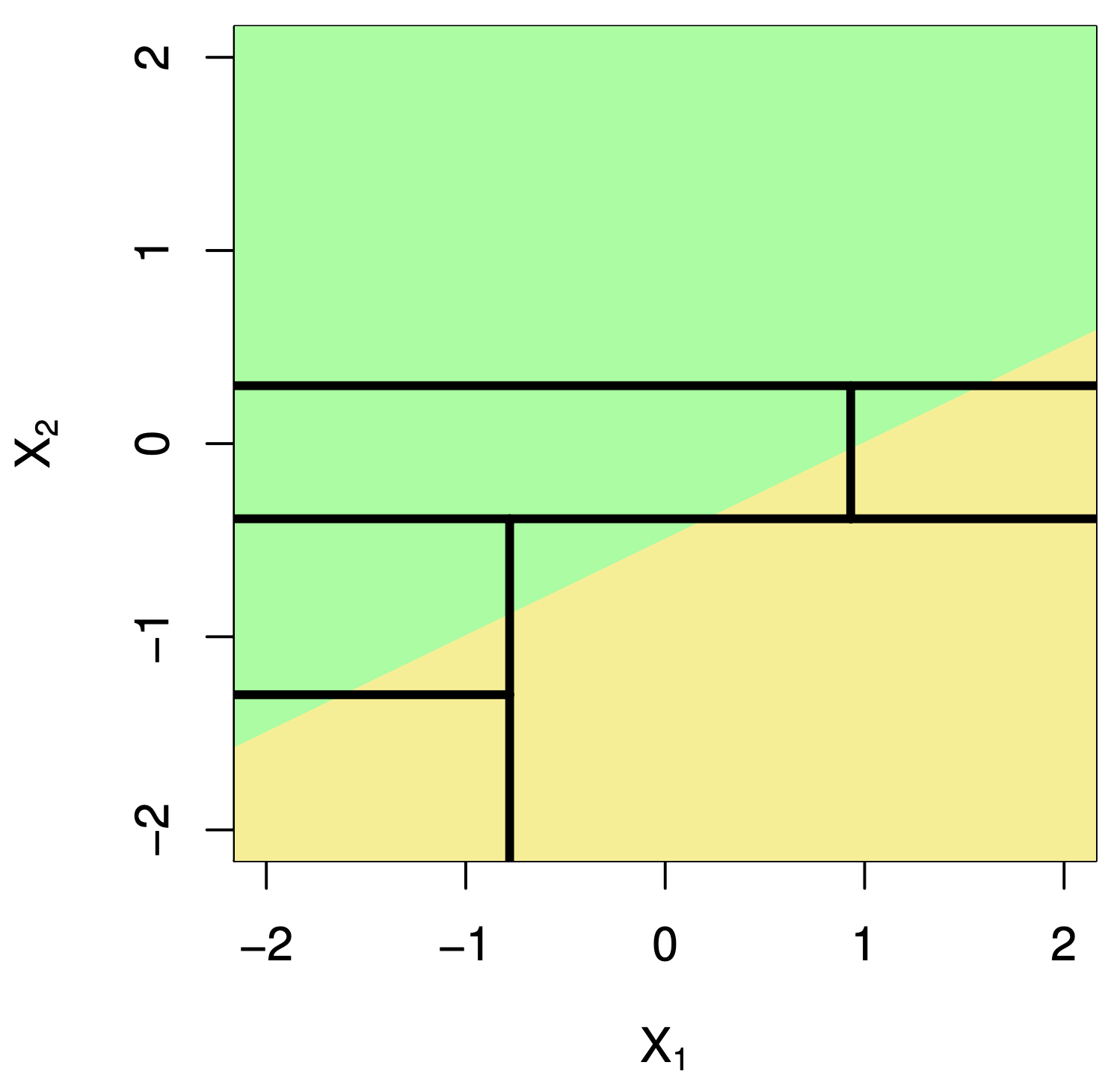

Classification Problems. The response is categorical and involves K different categories. For example, the brand of a product purchased (A, B, C) or whether a person defaults on a debt (yes or no).

The predictors (\(\boldsymbol{X}\)) can be numerical or categorical.

Comments

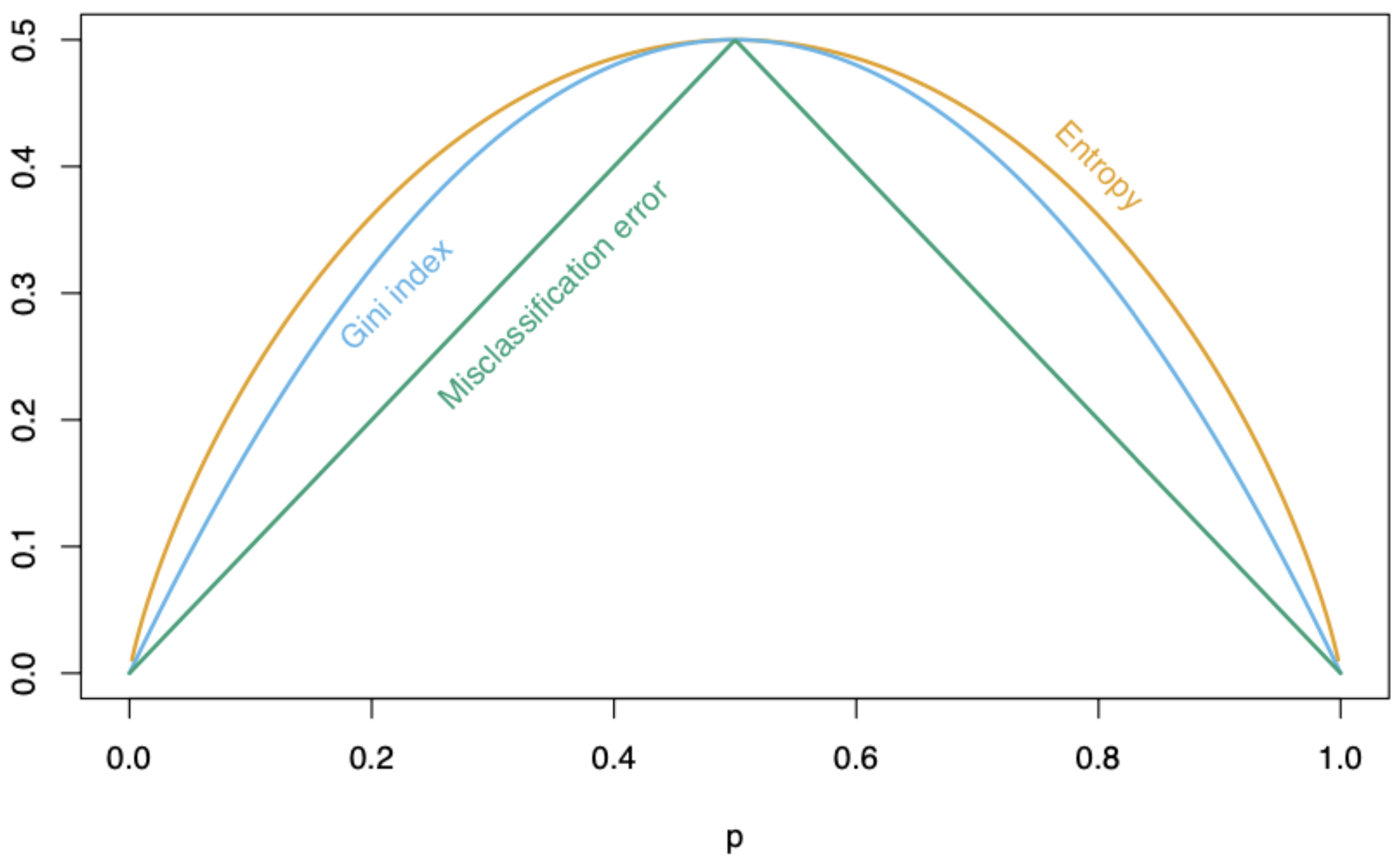

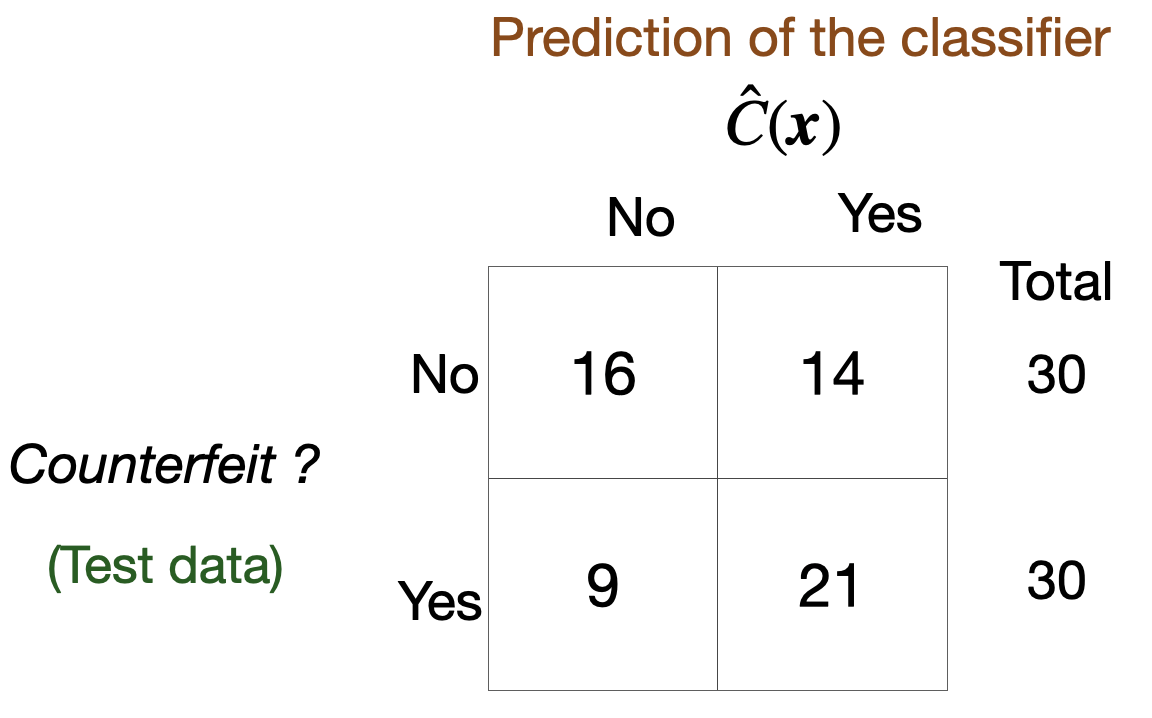

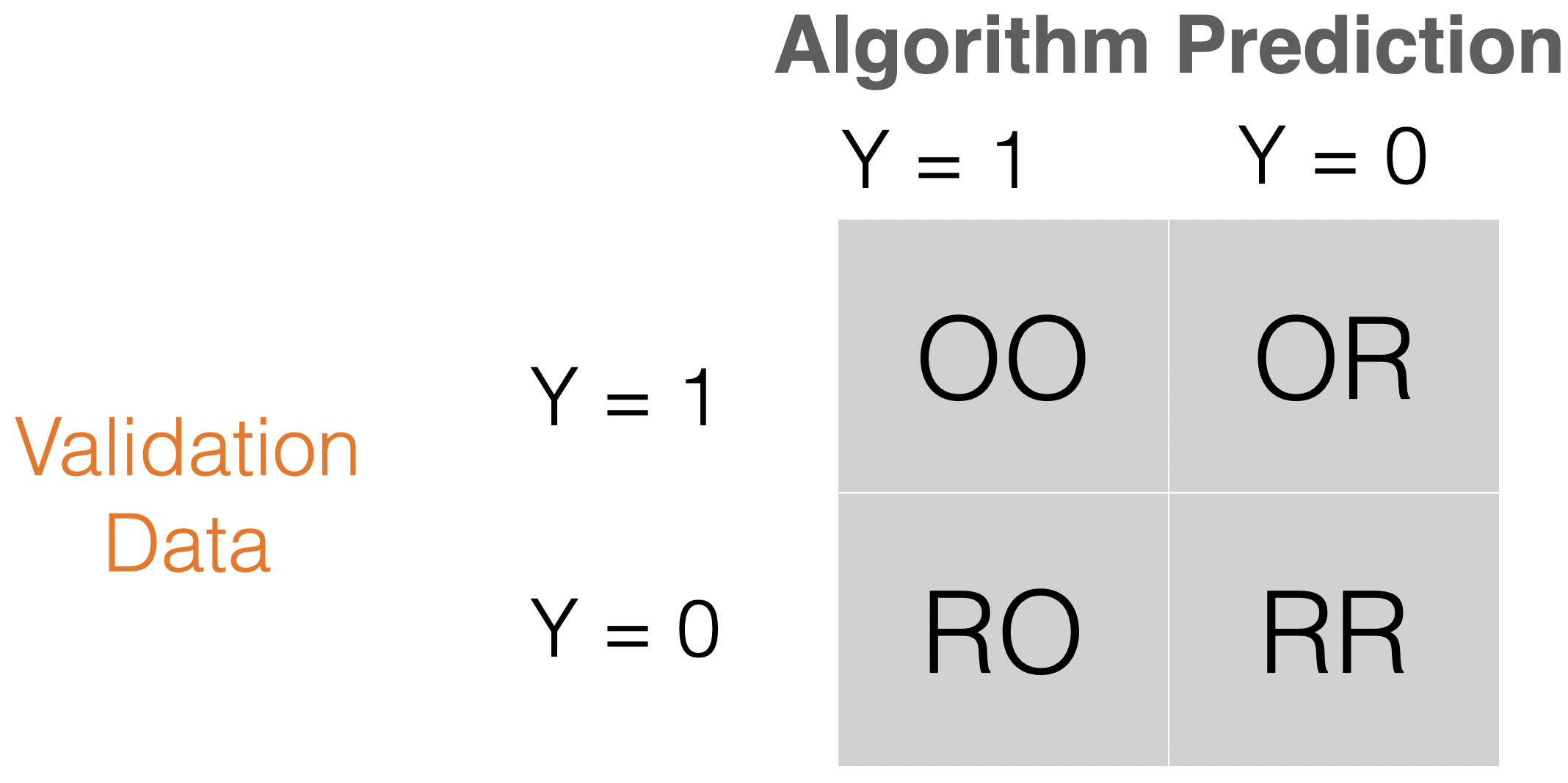

Accuracy is easy to calculate and interpret.

It works well when the data set has a balanced class distribution (i.e., cases 1 and 0 are approximately equal).

However, there are situations in which identifying the target class is more important than the reference class.

For example, it is not ideal for unbalanced data sets. When one class is much more frequent than the other, accuracy can be misleading.